As-Built But-For Schedule Delay Analysis

This article discusses topics such as: why the application of the As-Built But-For Schedule Delay Analysis methodology is appropriate, the As-Built Calculation Schedule, quantification of delays, interpreting the results of removing delays from the As-Built Calculation Schedule, and overcoming criticisms of the As-Built But-For Schedule Delay Analysis Method.

1. INTRODUCTION

An As-Built But-For Schedule Delay Analysis1 (ABBF) is a retrospective CPM schedule delay analysis technique that determines the earliest date that the required mechanical completion activity, project completion activity, or various milestone activities could have been achieved but-for the owner-caused compensable delays that occurred during the project.2 The amount of owner-caused delay determined from the ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis quantifies the contractor’s entitlement to receive compensable delay damages. Similarly, the analysis could determine the earliest date that the various completion activities could have been achieved but-for the contractor-caused noncompensable delays that occurred during the project.

While the ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis can be calculated using the entire period of the project as one as-built schedule,3 the ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis can also be performed in windows or periods of time, where the as-built schedule and its then current critical path can be analyzed separately for each window or period, and cumulatively for the project.4

The ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis is calculated using the actual start and finish dates and actual work sequences of activities in the as‑built schedule to determine if delay to the as‑built critical path5 during the analysis period has occurred. The as-built critical path during each schedule window may be different from the planned critical path at the start of each schedule window, due to delays, scope changes, etc., that have occurred during the schedule window. Therefore, the ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis focuses on responsibility for delays that affected the dynamic nature of the as-built critical path of the schedule window rather than delays that affected the planned critical path at the beginning of the schedule window.

In contrast, the Time Impact Analysis (TIA) or the Update Impact Analysis (UIA) adds impacts to the planned schedule to measure any potential delay. The TIA is calculated on schedules which are statused up through the day before each impact first occurred. The UIA is calculated on schedules which are statused at the beginning of a specific window or impact period, typically the monthly schedule updates prepared during the project. Often, a schedule analyst performs a TIA or UIA for the calculation of an extension of time. However, the analyst may incorrectly conclude that the total time extension entitlement or total actual delay is compensable. This conclusion may be incorrect if the analyst fails to address concurrent delays in the as-built schedule, or if the time extension is longer than the actual delay that occurred as the result of acceleration or other delay mitigation.6 The ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis addresses concurrent delays, and the net period of owner-caused delay may be compensable after concurrency of contractor-caused and other excusable delays are addressed.7 Therefore, to avoid an incorrect conclusion, a TIA or UIA can be used to calculate the time extension to which the contractor is entitled as a result of owner-caused and other excusable delays, and the ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis can also be used to determine the compensable delay days to which the contractor is entitled as a result of owner-caused delays.

The ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis is typically more difficult to perform than the TIA or UIA because most CPM software programs regard as-built dates as historical events fixed in time. As a result, most CPM software programs will not permit but-for analysis models to be run on schedules containing actual dates. Consequently, the as-built schedule must be converted to an as-planned format containing “planned” dates that correspond to the as-built schedule but are driven by logic and activity durations. This conversion step is used to create an As-Built Calculation Schedule that can collapse as delays are removed.8

The ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis is performed by first removing owner-caused delays from the As-Built Calculation Schedule and recalculating the project completion date. Contractor-caused (noncompensable) and excusable/noncompensable delays are left in the As-Built Calculation Schedule. The As-Built Calculation Schedule with owner-caused delays removed is used to determine the compensable time period between the actual project completion date and the as-built but-for completion date.

Next, contractor-caused delays are removed from the original As-Built Calculation Schedule and the project completion date is recalculated. Owner-caused (compensable) and excusable/ noncompensable delays are left in the As-Built Calculation Schedule. The ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis that removes contractor-caused delays is used to determine the time period between the actual completion date and the as-built but-for completion date for assessment of liquidated damages by the owner.9

The conclusions derived from the ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis are described in more detail in Section 5 of this article.

The following information is provided in this article:

- Why the application of the ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis methodology is appropriate;

- The As-Built Calculation Schedule;

- Quantification of delays;

- Interpreting the results of removing delays from the As-Built Calculation Schedule; and

- Overcoming criticisms of the ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis Method.

2. WHY THE APPLICATION OF THE AS-BUILT BUT-FOR DELAY ANALYSIS METHOD IS APPROPRIATE

The ABBF Schedule Analysis is commonly used in the construction industry.10 It has been said that:

The as-built but-for method is popular with both developers and contractors because, unlike the as-planned impacted method, it is based on consideration of the actual build times and can be used for determining not only the period of excusable delay, but also the period over which loss and expense may have been suffered.11

The same industry reference describes the cause-effect relationship derived from the use of the ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis method:

The effect of the causal event on the key dates and completion date is then the difference between the date calculated before the event was subtracted, and that calculated after the event was subtracted.12

The justification for the ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis is that it focuses on what was actually critical over the life of the project:13

[O]ne of the arguments frequently encountered is the issue of hindsight pricing of delays, as opposed to current or contemporaneous pricing of delays. We might describe this as the need to answer a requirement or argument for the use of the but for test in the evaluation process. This should be satisfied if delays are evaluated update by update both at the beginning and end of updates, not only to identify where the critical path is located at the inception of the period but also to locate the critical path during the period and to assure that the critical path was not overtaken by other delays (or concurrent with other critical path delays) during the month in question.14

It is a common misconception in the construction industry that if the contractor is entitled to an extension of time, then it is also automatically entitled to be compensated for the additional time that it has taken to complete the contract.15 It is usually not.

An additive delay analysis, such as the TIA or UIA, by itself does not provide an answer to the issue of compensable delay. If a contractor incurs additional costs that are caused by both owner delay and concurrent contractor delay, then the contractor should only recover compensation to the extent it is able to separately identify the additional costs that were only caused by the owner delay. If it would have incurred the additional costs in any event as a result of concurrent contractor-caused delays, the contractor will not be entitled to recover those additional costs unless provided otherwise in the contract.16 Therefore, the ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis is often performed to address the issue of compensable delay net of concurrent contractor-caused delay on the as-built schedule, which the TIA and UIA do not analyze properly.

AACE International also acknowledges that an entitlement to an extension of time does not provide the contractor with a right to delay compensation:

Note that the terms, compensable, excusable and non-excusable, in current industry usage, are from the viewpoint of the contractor. That is, a delay that is deemed compensable is compensable to the contractor, but non-excusable to the owner. Conversely, a non-excusable delay is a compensable delay to the owner since it results in the collection of liquidated/stipulated damages.17

A neutral perspective on the usage of the terms often aids understanding of the parity and symmetry of the concepts. Thus entitlement to compensability, whether it applies to the contractor or the owner, requires that the party seeking compensation show a lack of concurrency if concurrency is alleged by the other party. But for entitlement to excusability without compensation, whether it applies to the contractor or the owner, it only requires that the party seeking excusability show that a delay by the other party impacted the critical path.

Based on the symmetry of the concept, one can say that entitlement to a time extension does not automatically entitle the contractor to delay compensation. In addition to showing that an owner-delay impacted the critical path, the contractor would have to show the absence of concurrent delays caused by a contractor-delay or a force majeure delay in order to be entitled to compensation. [Emphasis added.]

A contractor delay concurrent with many owner delays would negate the contractor’s entitlement to delay compensation. Similarly, one owner delay concurrent with many contractor delays would negate the owner’s entitlement to delay compensation, including liquidated/stipulated damages. While in such extreme cases the rule seems draconian, it is a symmetrical rule that applies to both the owner and the contractor and hence ultimately equitable.18

Thus, the ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis quantifies the net effect, i.e., the contractor’s entitlement to extended time-related costs, of the absence of certain noncompensable delays to the as-built critical path. For example, in Canon Construction Corporation, the ASBCA provided a clear and logical description of how the but-for schedule can be utilized in the proof of extended duration claims:

A proper determination of this appeal required at the outset that the Board determine the date, as precisely as possible, upon which the appellant would have completed the contract work but for delays which might have been due either to Government fault or the performance of changed work. The next determination must be the actual date of the completion of the work. The difference between the two dates establishes the extended period of performance for which appellant would be entitled to be paid for extended fixed overhead costs.19

Often, the CPM schedule that is developed by the contractor for a complex project contains thousands of activities and multiple critical and near critical paths that need to be examined for delays. Concurrent owner-caused delays and contractor-caused delays to the actual sequence of the contractor’s work activities also need to be examined before the contractor’s entitlement to delay compensation can be determined. Thus, the ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis is an appropriate methodology for this retrospective delay analysis on a complex CPM schedule. Any other form of as-planned vs. as-built delay analysis comparison to determine compensable delay entitlement may not properly deal with concurrent delay and float issues in a sufficiently detailed manner to yield reliable results.

3. THE AS-BUILT CALCULATION SCHEDULE

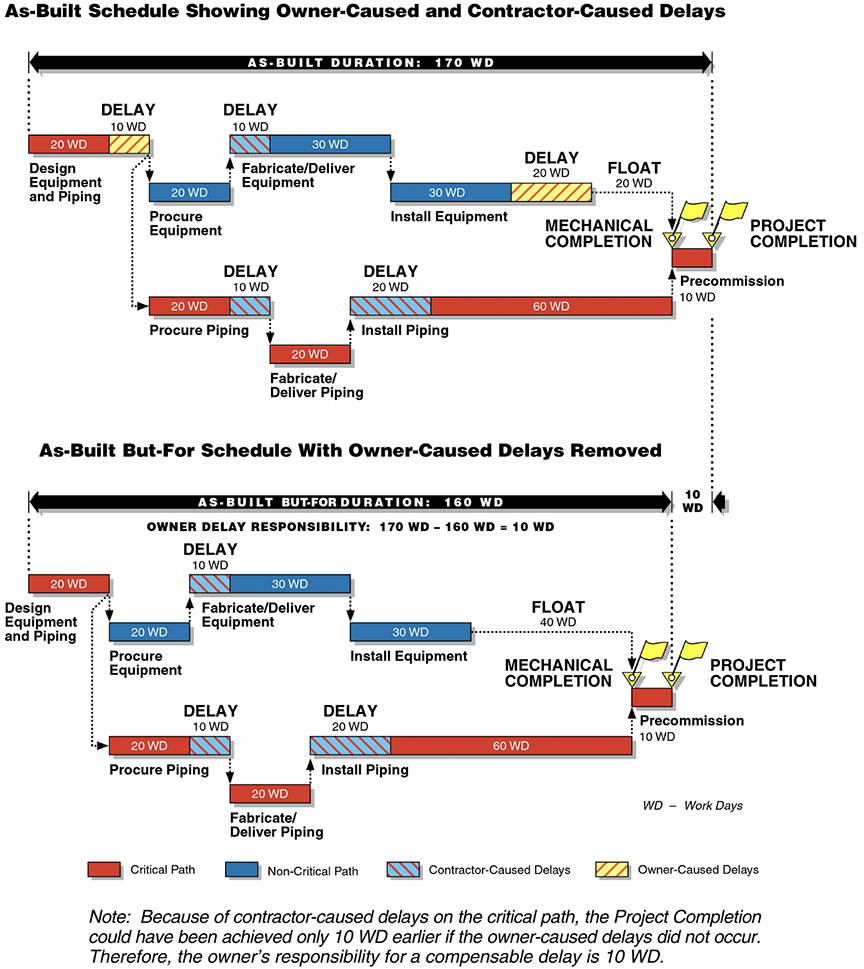

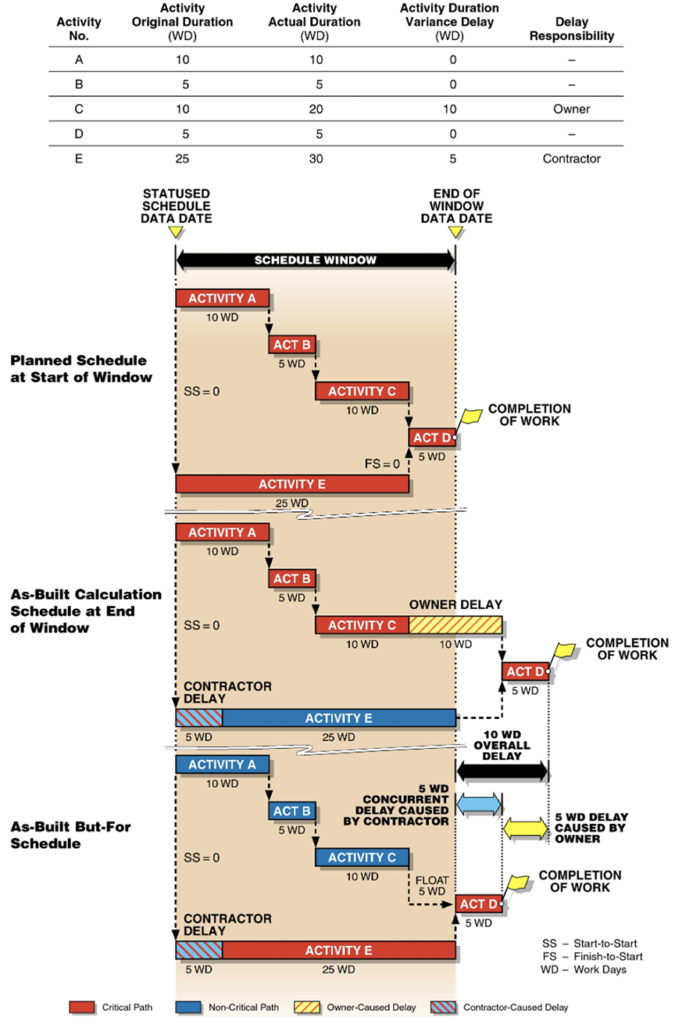

Figure 1 illustrates the ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis methodology. First, a model of the as-built schedule, which is called the As-Built Calculation Schedule, is developed with schedule logic and activity durations that calculate the same start and finish dates as the as-built dates in the as-built schedule. However, these dates are determined by the as-built logic and actual activity durations rather than the locked-in actual start and finish dates of the as-built schedule. The owner-caused and contractor-caused delays are then identified in the As-Built Calculation Schedule. The owner-caused delays are removed from the As-Built Calculation Schedule, leaving the contractor-caused delays and other excusable but noncompensable delays in the As-Built Calculation Schedule. In this example, the calculated project completion date collapses to an earlier completion date by only 10-work days because other delays that were caused by the contractor would prevent the project from being completed any earlier than a reduced duration of 10-work days. Therefore, the owner’s responsibility for compensable delay is 10-work days, although the sum of the periods of actual delay was longer, because of delays that were in the as-built schedule for which the owner is not responsible.

Figure 1

As-Built But-For Schedule Analysis Methodology

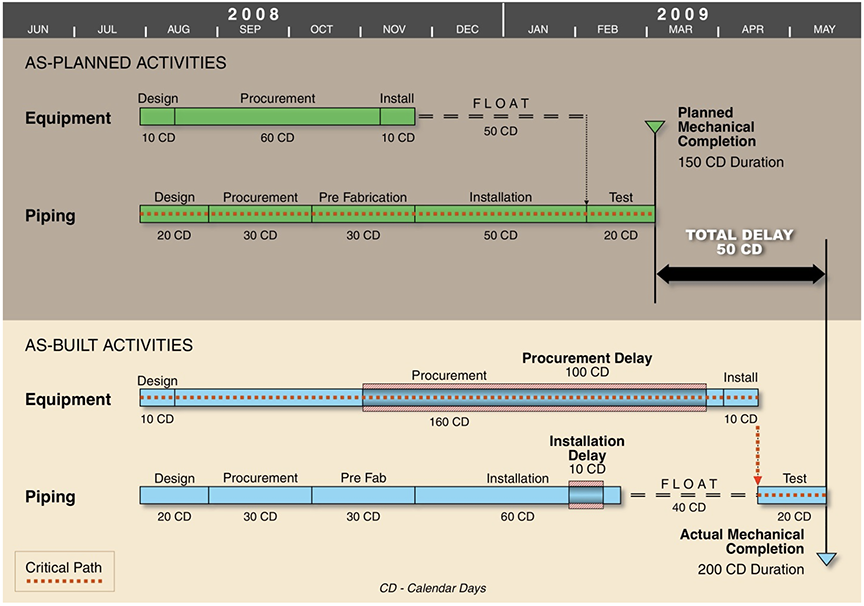

An analysis that only focuses on critical path work at the beginning of the window risks ignoring the real delay to Mechanical Completion, and ultimately to Project Completion.20 For example, Figure 2 shows an excerpt from a schedule in which piping activities are depicted that were on the critical path to Mechanical Completion at the start of the window. However, because of a procurement delay and to the equipment activities during the analysis window, the equipment activities became the as-built critical path of the project at the end of the analysis window. If the analyst had only analyzed the delays to the planned critical path at the start of the analysis period, an incorrect conclusion as to the cause of critical path delays would have been made.

Figure 2

Critical Path at the Beginning of a Window May Be Different from

the As-Built Critical Path at the End of a Window

The purpose of the As-Built Calculation Schedule is intrinsic to a CPM schedule model. If the schedule dates were based on fixed as-built dates, the effect of removal of delays could not be determined. However, if delays to activity relationships and durations are removed from the As-Built Calculation Schedule, whose dates are based on actual activity durations and logic, the schedule could then be recalculated to determine when the Project Completion date could have been achieved “but-for” the owner-caused delays that were removed from the As-Built Calculation Schedule.

To develop the As-Built Calculation Schedules for each window, an examination for out-of-sequence work should be made of the logical relationships in the statused schedules that depicted the actual manner in which the work was accomplished during each window. Often, the actual sequence of work that was examined at the end of the window was different from the contractor’s planned sequence of work at the beginning of the window. Therefore, the logical relationships between the schedule activities in the as-built schedule at the end of a window are different from the planned logical relationships between the schedule activities at the beginning of the window.

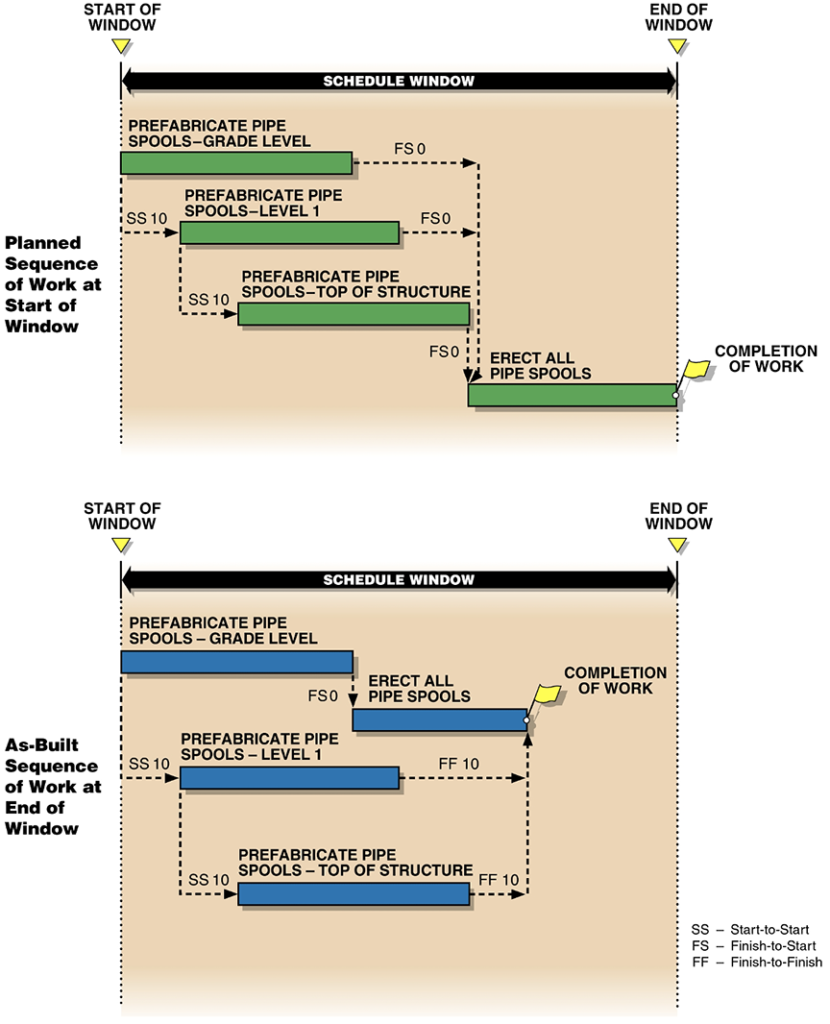

As a hypothetical example, as shown in the planned sequence of work in Figure 3, the erection of all pipe spools on a project may have been planned to start on the next day after the finish of prefabrication of all pipe spools needed for the Grade Level, Level 1, and the Top of Structure level. However, for various reasons, the contractor may have started the erection of pipe spools well before all pipe had been prefabricated into pipe spools. Therefore, rather than a finish-to-start (F-S) relationship between the completion of all pipe spools and the erection of all pipe spools as depicted in the planned sequence of work at the start of the window, the erection of pipe spools on each level was actually performed with a finish-to-start relationship after the prefabrication of pipe spools on the grade level was completed. The erection of the pipe spools on the other two levels actually commenced when the pipe was fabricated for those levels such that a FF‑10 relationship was required from the completion of the pipe fabrication on each level to the completion of the Erection of All Pipe Spools activity. This change is shown in the as-built sequence of work in Figure 3. If the actual sequence of work indicates that a different logical relationship model between the activities is warranted, the analyst would adjust the schedule logic in the As-Built Calculation Schedule to represent the as-built conditions.

Figure 3

Logic Relationships at the Start of a Window May Change During the Window

4. QUANTIFICATION OF DELAYS

In using the As-Built But-For Schedule Delay Analysis, the durations of owner-caused delays are quantified to model their effect by removing them from the As-Built Calculation Schedule. Actual delays in the As-Built Calculation Schedule are quantified from the comparison of the planned and actual activity durations and relationship lag durations, as measured by the activity data at the end of the window and the planned activity durations and relationship lags at the beginning of the window. These duration and lag variances are then used to model the effect of the delays by removing the quantified delays from the As-Built Calculation Schedule for each window.21

Figure 4 provides a graphic explanation of how an owner-caused delay is removed from the As-Built Calculation Schedule to model the effect of an owner-caused duration delay that was quantified by a duration variance calculation. In this case, a 10-work day owner-caused delay and a 5-work day contractor-caused delay were identified in the window by comparing the original and actual activity durations during the window. An As-Built Calculation Schedule was prepared to model the owner-caused and contractor-caused delays. If the 10‑work day owner-caused delay is then removed from the schedule network, the Completion of Work milestone collapses to a date which is only 5 work days beyond the original Completion of Work date because the 5-work day contractor-caused delay becomes the remaining driving critical path delay. Therefore, the contractor is only entitled to a 5-work day compensable delay.

Figure 4

Example of an Owner-Caused Delay Quantified by a Duration Variance Calculation

5. INTERPRETING THE RESULTS OF REMOVING DELAYS FROM THE AS-BUILT CALCULATION SCHEDULE

By removing delays that were caused by the owner from the activity durations and from the activity lag relationship durations, the As-Built Calculation Schedule for each schedule window may or may not collapse to simulate the effect of the removal of delays on the various completion date(s) being examined.

If the As-Built Calculation Schedule completion date collapses to an earlier completion date after the owner-caused delays are removed, the net duration of the schedule collapse is the amount of compensable delay days for which the owner may be responsible. These delays may have caused increases to the contractor’s home office overhead costs, and/or the contractor’s and its subcontractors’ field office overhead costs.22

If the As-Built Calculation Schedule collapses to the projected completion date at the start of the schedule window after the owner-caused delays are removed, the total amount of delay in that window was solely caused by the owner and may be compensable because there were no concurrent delays to the critical path that were caused by the contractor.

If the As-Built Calculation Schedule does not collapse at all, or only collapses partially (i.e., not to the original projected completion date at the start of the window), the owner-caused delays that were removed were either:

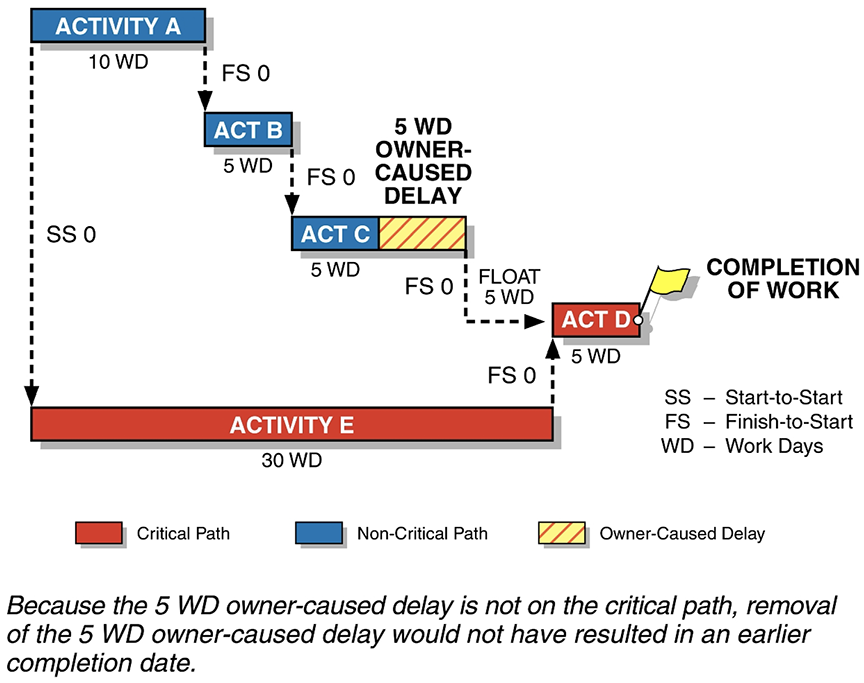

- Not on the critical path and, therefore, the owner-caused delay would not have affected the completion date(s), as shown by Figure 5. In this case, the 5-work day owner-caused delay affected Activity C, which still had 10 work days of available float after the delay occurred because the Activity E and Activity D were the actual critical path to the Completion of Work; or

Figure 5

Owner-Caused Delays Were Not on the Critical Path

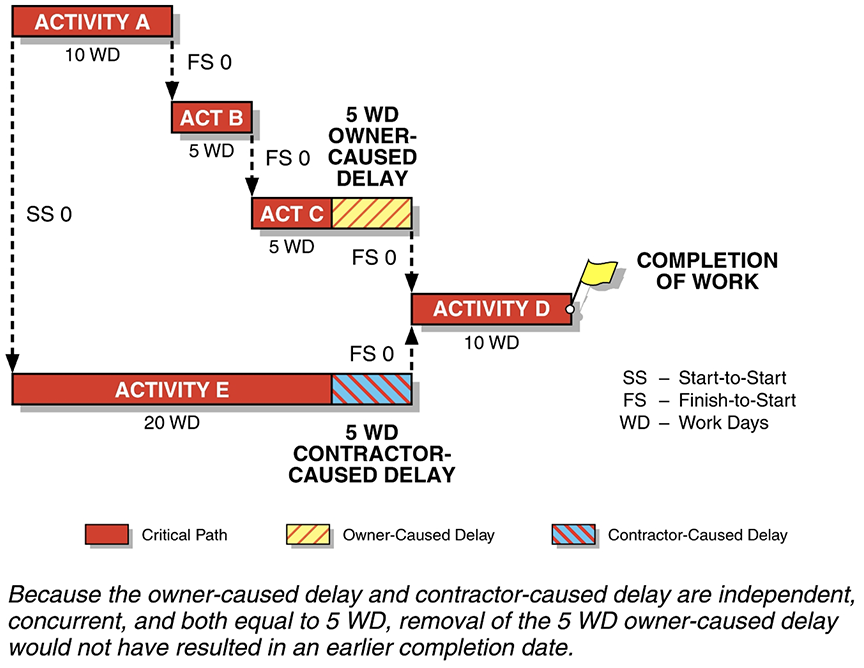

- Concurrent with contractor-caused delays or other noncompensable but excusable delays that were also on the as-built critical path which prevented the schedule completion date from collapsing to the original projected completion date at the start of the window, as shown by Figure 6. In this example, the 5-work day owner-caused delay and the 5-work day contractor-caused delay affected two parallel activity paths, were independent delays, and both delays would have extended the completion of the project. Therefore, because of the contractor-caused delay being fully concurrent with the owner-caused delay, the completion date(s) would not have occurred any earlier if the owner-caused delays had not occurred; or

Figure 6

Owner-Caused Delays Were

Fully Concurrent with Contractor-Caused Delays

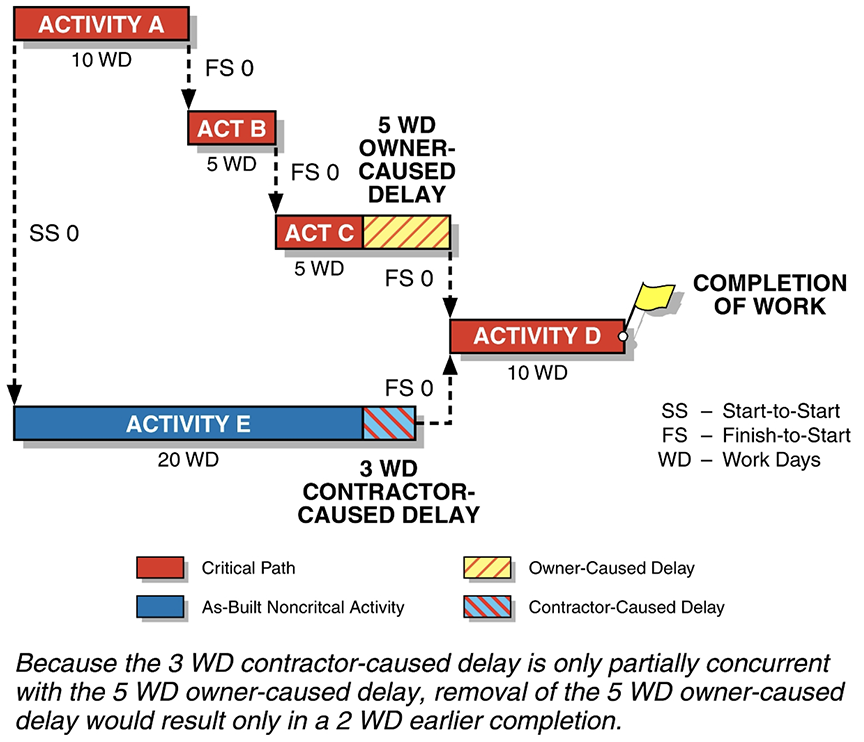

- Concurrent in part, but not for the entire owner-caused delay period, with contractor-caused delays or other noncompensable but excusable delays that were also on the as-built critical path which prevented the scheduled Completion of Work date from totally collapsing to the original projected Completion of Work date at the start of the window, as shown by Figure 7. In this example, a 5‑work day owner-caused delay occurred on a parallel activity path (Activity A, B and C) to Activity E, which experienced a 3-work day contractor-caused delay. Removal of the 5-work day owner-caused delay would only allow the schedule to collapse by 2 work days because of the parallel contractor-caused delay. Therefore, because of the contractor-caused delay being partially concurrent with the owner-caused delay, the Completion of Work date(s) would have occurred earlier if the owner-caused delay had not occurred only to the extent that the owner-caused delays were not concurrent with the contractor-caused delays.

Figure 7

Owner-Caused Delays Were Partially Concurrent with Contractor-Caused Delays

Therefore, delay compensation would only be applicable for the number of days that the As-Built Calculation Schedule did collapse in each window after the owner-caused delays are removed.

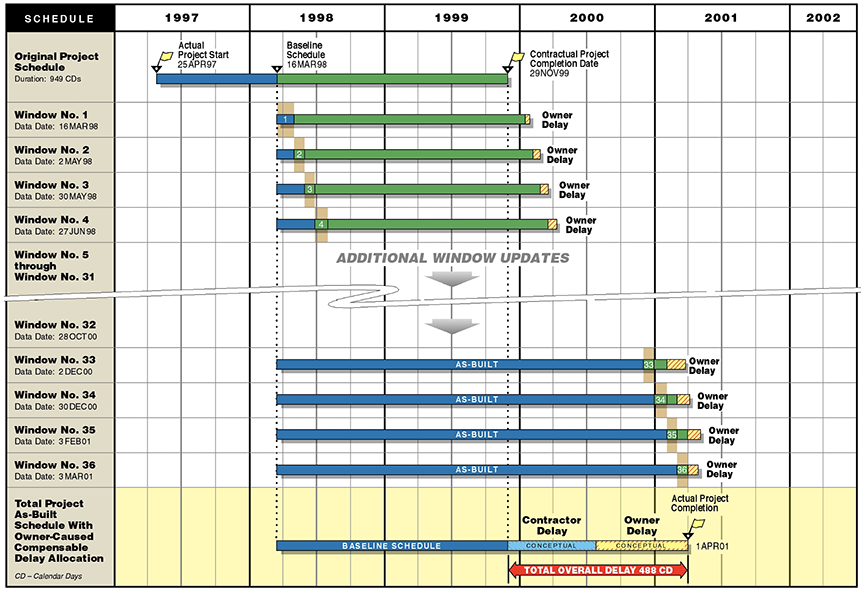

The net overall compensable delay is determined by adding the cumulative number of compensable delay days derived from the as-built but-for calculations in each window, as shown conceptually in Figure 8.

Figure 8

Net Overall Compensable Delay for All Windows

(Conceptual)

6. OVERCOMING CRITICISM OF THE ABBF SCHEDULE DELAY ANALYSIS METHOD

Notwithstanding the inclusion by AACE International in its Recommended Practice R29-03, the ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis method has been criticized by some commentators. In the following paragraphs, the debate regarding this form of construction project schedule analysis is considered and an explanation is provided as to how a properly prepared ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis would take into account and address those concerns.

The primary concern is in connection with the alleged subjectivity that may occur in creating the As-Built Calculation Schedule.23 To avoid subjectivity in its development of the As-Built Calculation Schedules, the analyst should apply consistent rules for the establishment of the as-built logic in each window. These rules should be applied before any knowledge is obtained as to what activities have been delayed, when the delays occurred, and which party may be responsible for those delays. These rules should also identify driving predecessor logic based on the contractor’s planned logic and the actual timing of completion of predecessor activities, and not based on what the analyst believes may have been the driving predecessor logic.

Some analysts may argue that the application of the ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis method is not forward looking, chronological, and cumulative. However, comments of this nature are often based on the premise that the but-for analysis is performed using only one as-built schedule window that comprises the entire duration of the project. That is not the case in the windows application of this method, as described in AACE International’s 29R-03, MIP 3.9. Application of the method on a windows basis considers the dynamic nature of the critical path as the work moves forward in each window. The results are tallied on a cumulative basis if the effects of a delay occur in more than one window. Thus, the but-for analysis is focused on the impacting events that affect the as-built critical path throughout the project, and cumulatively for the project.

Others may contend that an after-the-fact approach, such as an ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis, may fail to address the need to consider time extensions on a real time basis. However, time extensions for owner-caused delays such as Change Orders and other events for which the Owner may be responsible can be separately analyzed using the TIA or UIA methods. The application of the ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis methodology is solely for the purpose of calculating the contractor’s entitlement to compensable delay, which is different from the contractor’s entitlement to a time extension, and perhaps the owner’s entitlement to liquidated damages.

Likewise, commentators have noted that the ABBF construction project schedule analysis assumes that the project would have to be built the exact same way if the various project delays had not arisen, and the contractor made no attempt to mitigate the effect of delays.24 This ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis assumption is not unlike the assumption in a TIA or UIA, wherein it is assumed that the contractor would design and build the remaining activities in the project schedule, after the impact is inserted, in the same exact sequence that it planned before experiencing changes in its scope of work or other impacting events that affect the schedule. Models by their nature keep certain parameters the same and predict results by modeling the effect of changes to other parameters. The TIA, UIA, and ABBF Schedule Delay Analyses are modeled analyses and maintain certain parameters and evaluate the result based on changing other parameters. One can always second guess what could have been done had a delay not occurred. The ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis models what was actually done, but without the owner-caused delays.

Certain practitioners of this technique have performed the analysis by identifying and quantifying only owner-caused delays. The underlying premise being that the contractor is, by definition, then responsible for the balance of the extended duration experienced by a particular activity. Unfortunately, this approach overlooks the fact that, in many instances, extended durations that superficially appear to result from contractor delays are actually “pacing delays” that were a direct result of owner-caused delays and impacts. Extensive relevant construction experience is, therefore, required to accurately adjust activity durations that appear to be contractor delays but are really the direct result of extended durations that were caused by the owner. Contractors will often temporarily divert resources to other job activities in an effort to avoid or minimize force reductions, thereby prolonging the completion of delayed work. Therefore, determining the duration of activity delay by simply comparing planned and actual performance is inappropriate. An argument may be made that these pacing delays would not have occurred if owner delays had not occurred.25 If the analyst found evidence that the contractor deliberately slowed down its work on activity(s)26 which were delayed concurrently with owner-caused delays to another activity(s), then the analyst should consider the possibility that those activities were “pacing delays.” If both owner- and contractor-caused delays are properly identified, this methodology has considerable merit.

Another question is whether work activities were performed continuously between the actual start date for an activity and the actual finish date for an activity, or in fact the work may not have been performed continuously.27 The application of the ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis method should compare the planned vs. actual duration of activities as well as the lag variance between activities. The variances in overall activity durations and lag durations should then be examined for all potential causes of delay that may have been caused by the owner’s delays. Any remaining activity variances are then examined for documentation evidencing pacing delays. If the evidence exists regarding deliberate pacing, those delays are also allocated to the owner. The project record should also be examined for evidence of potential contractor-caused delays to the activities on the critical and near critical paths. By using this comprehensive approach, the analyst is able to assign delays for which both the owner is responsible and delays for which the contractor is responsible. If the contractor did not perform the work continuously, and all owner-caused delays are allocated, the additional delay durations are the contractor’s responsibility, whether the work on the activity was performed continuously or not.

It is also incumbent on the analyst to verify the accuracy of the as-built dates for the schedule activities.28 If certain dates are found to be inaccurate, the analyst should correct those dates in the as-built schedule and provide documentation to support the changed dates.

Another common misuse of the ABBF construction project schedule analysis is the arbitrary extraction of delays from the As-Built Calculation Schedule. Furthermore, the delay extraction process can be inappropriately manipulated to cover up the effect of the claimant’s delays. These deficiencies can usually be discovered and corrected, however, by running several iterations of the ABBF Schedule Delay Analysis, extracting owner-caused and contractor-caused delays separately and jointly, to more accurately evaluate the impact of each party’s delays to the project completion schedule.

Nevertheless, because this technique considers multiple paths in the analysis of schedule delay, it is popular with both owners and contractors in their defense against, and in pursuit of, extended duration claims. From the owner’s perspective, a contractor’s compensable claim is recognized only to the extent that no “other” parallel float path becomes critical. This is determined by removing owner-caused delays from the “critical path” until another path becomes critical. At that point, the compensable delay claim is halted, and the other float paths are examined. If no owner-caused delay can be found on other paths, a contractor-caused concurrent delay may exist which denies the contractor compensation for the balance of the overall project delay period.

About the Author

Richard J. Long, P.E., P.Eng., is Founder of Long International, Inc. Mr. Long has over 50 years of U.S. and international engineering, construction, and management consulting experience involving construction contract disputes analysis and resolution, arbitration and litigation support and expert testimony, project management, engineering and construction management, cost and schedule control, and process engineering. As an internationally recognized expert in the analysis and resolution of complex construction disputes for over 35 years, Mr. Long has served as the lead expert on over 300 projects having claims ranging in size from US$100,000 to over US$2 billion. He has presented and published numerous articles on the subjects of claims analysis, entitlement issues, CPM schedule and damages analyses, and claims prevention. Mr. Long earned a B.S. in Chemical Engineering from the University of Pittsburgh in 1970 and an M.S. in Chemical and Petroleum Refining Engineering from the Colorado School of Mines in 1974. Mr. Long is based in Littleton, Colorado and can be contacted at rlong@long-intl.com and (303) 972-2443.

1 Sometimes this methodology is called a Collapsed As-Built Schedule Analysis.

2 Unless specified otherwise in the contract, concurrent contractor-caused delays and other excusable delays such as force-majeure delays, are normally noncompensable delays and, therefore, must be considered in an analysis to determine how much of the overall delay is compensable. By analyzing both compensable and noncompensable delays in the as-built schedule, the analyst can determine if they are on the same or concurrent critical path and also would have delayed the project. If compensable and noncompensable delays are concurrent, and unless otherwise specified in the contract, neither the owner nor the contractor is entitled to delay damages.

3 See AACE International’s Recommended Practice 29R-03 Forensic Schedule Analysis, MIP 3.8, April 25, 2011.

4 Id., MIP 3.9.

5 See Section 3 herein for a discussion of the calculation of the as-built critical path.

6 Contractor-caused problems may have also disrupted the contractor’s work and delayed the critical path of the project.

7 Owner-caused delays may not be compensable if the contract contains a “no damage for delay” clause.

8 See Section 3 for a more-detailed explanation of the As-Built Calculation Schedule.

9 The TIA and UIA can also be used to determine the owner’s entitlement to liquidated damages if the actual completion date is later than the impacted completion date; the difference being the number of days to which liquidated damages can be applied.

10 See, for example, Wickwire, Jon M., Thomas J. Driscoll, Stephen B. Hurlbut and Scott B. Hillman, Construction Scheduling: Preparation, Liability and Claims, 2nd Edition, Aspen Law & Business, New York, 2003, Section 9.08[I] ‘But-For’ Test for Extended Duration Claims, pp. 372-374, and Section 9.06[B] But For Analysis/Collapsed As-Built, pp. 272-273; also see Pickavance, Keith, Delay and Disruption in Construction Contracts, 3rd ed., T&F Informa (UK) Ltd, London, 2005, p. 564, paragraph 14.292; “The Society of Construction Law Delay and Disruption Protocol,” Oxford, October 2002, Section 4.7, p.47; Keane, P.J. and A.F. Caletka, Delay Analysis in Construction Contracts, Wiley-Blackwell, 2008, Section 4.2.4, pp. 140-150; “Forensic Schedule Analysis,” AACE International Recommended Practice No. 29R-03, Method Implementation Protocol 3.9: Modeled, Subtractive, Multiple-Base Schedule Analysis,” April 25, 2011. Long International has used its As-Built But-For Schedule Analysis methodology on numerous retrospective delay analyses as experts in arbitrations and litigations regarding projects in many counties, including Argentina, Canada, England, Indonesia, The Netherlands, Norway, Saudi Arabia, Trinidad and Tobago, United States, and Venezuela. Long International’s As-Built But-For Schedule Delay Analysis methodology is based on MIP 3.9.

11 See Pickavance, p. 566, paragraph 14.306.

12 See Pickavance, p. 564, paragraph 14.293.

13 See Wickwire, et. al., Section 9.10 Safeguards for Establishing Delay Quantum Baselines, pp. 413-414.

14 Id.

15 See “The Society of Construction Law Delay and Disruption Protocol,” Oxford, October 2002, paragraph 1.6.3, page 18, which states, “It is a common misconception in the construction industry that if the Contractor is entitled to an EOT, then it is also automatically entitled to be compensated for the additional time that it has taken to complete the contract. Under the common standard forms of contract, the Contractor is nearly always required to claim its entitlement to an EOT under one provision of the contract and its claim to compensation for that prolongation under another provision. There is thus no absolute linkage between entitlement to an EOT and the entitlement to compensation for the additional time spent on completing the contract.” Also see Wickwire, et. al., Section 9.08[G]1, pp. 350-355, Key Issues Involving Concurrent Delay and Extended Duration Claims, and Proof for Time Extensions Versus Proof for Compensable Delay.

16 See “The Society of Construction Law Delay and Disruption Protocol,” Oxford, October 2002, Core Principles Related to Delay and Disruption, item 10, page 7, and Guidance Section 1.10.1 and 1.10.4.

17 This assumes that the contract includes an assessment of liquidated damages for the delayed completion of work by the contractor. In the absence of liquidated damages, the owner is often entitled to compensation for its actual damages.

18 See AACE International Recommended Practice No. 29R-03 Forensic Schedule Analysis, April 25, 2011, Section 4.1.C, pp. 100-101.

19 Canon Construction Corporation, ASBCA No. 16142, 72-1 BCA (CCH) 9,404 (1972).

20 The overall delay analysis is based on delay to Final Acceptance.

21 Either a Global vs. Stepped Removal of Delays can be used, depending on the detail needed for the analysis.

22 Actual time-related cost increases would still need to be demonstrated with evidence to prove that the contractor or its subcontractors actually incurred compensable delay damages.

23 See Wickwire, Jon M., Thomas J. Driscoll, Stephen B. Hurlbut and Scott B. Hillman, Construction Scheduling: Preparation, Liability and Claims, 2nd Edition, Aspen Law & Business, New York, 2003, Section 9.06[B] But For Analysis/Collapsed As-Built.

24 See Zack, James G., “But-For Schedules-Analysis and Defense,” AACE International Transactions, 1999, CDR.04.1.

25 See Zack, James G., “But-For Schedules-Analysis and Defense,” AACE International Transactions, 1999, CDR.04.1.

26 In such cases, the contractor should notify the owner of its intent to deliberately slow down work.

27 See Zack, James G., “But-For Schedules-Analysis and Defense,” AACE International Transactions, 1999, CDR.04.1.

28 Id.

Copyright © Long International, Inc.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Articles

Articles by our engineering and construction claims experts cover topics ranging from acceleration to why claims occur.

MORE

Blog

Discover industry insights on construction disputes and claims, project management, risk analysis, and more.

MORE

Publications

We are committed to sharing industry knowledge through publication of our books and presentations.

MORE