Differing Site Conditions: Clauses, Claims, & More in Construction

This paper covers contractual representations; Type I, Type II, and Type III differing site conditions; the contract absent a differing site conditions clause; and owner defenses.

1. INTRODUCTION

A “Differing Site Condition” (DSC) occurs when a construction contractor encounters a subsurface or otherwise concealed site condition that differs materially from what was indicated in the contract or from what would normally be expected. The term DSC was originally called “changed conditions.” Differing site condition is now used because its application has extended beyond underground conditions where it originated. The term “changed conditions” may be a misnomer in the case of DSC events because it generally does not refer to a change but to an existing condition at the time the contract was executed but which was not anticipated. Aboveground work or situations that involve renovation or rehabilitation of existing works may generate changed conditions claims. If an upstream contractor creates hardships in performance of downstream work or where the error of a third party causes damage to equipment, a changed condition claim may result.

The prospects for a contractor to recover after encountering a DSC are dependent on:

- The extent of the positive representations as to anticipated subsurface conditions that were made by the owner;

- The extent to which conditions encountered differed materially from those represented;

- The extent to which the contractor could have anticipated or observed the different conditions by a site visit, previous experience in the geographic area, etc.;

- The extent to which the contractor documented its assumptions regarding site conditions affecting the work as a basis of its cost estimate;

- The owner’s knowledge of the conditions actually encountered; and

- The extent to which the contractor provided written notice to the owner when the DSC was encountered.

2. CONTRACTUAL REPRESENTATIONS

The contract documents are critical to examining the validity of a claim for differing site conditions. First, do they describe a condition materially different than that actually found at the site? Second, do they contain disclaimers about site information provided by the owner either in the bid package or in separate documents? Do the disclaimers say something to the effect that the information provided by the owner is for reference only, is not part of the contract documents, cannot be relied upon for any reason, and does not give the contractor the right to file a claim?

The Federal government’s differing site conditions clause, two simple representative clauses, typical private owner clauses, as well as two forms of DSC clauses from international contract forms are discussed below. The remedies and procedures of the clauses are then compared.

Although the Federal government has contractually proscribed two types of DSCs, some regional mass transit agencies have adopted three types, with the third type being applicable to encountering unknown environmentally contaminated materials. Case law on this type of DSC to date is limited and, in the Federal arena, remains commonly addressed as at Type 2 differing site condition.

2.1 FEDERAL GOVERNMENT

All fixed‑price Federal government contracts for construction, dismantling, demolition, and/or removal of improvements, where the contract value is anticipated to exceed $25,000, must contain a differing site conditions clause (as it is now referred to).1 The standard DSCs clause of the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) states as follows:2

(a) The Contractor shall promptly, and before the conditions are disturbed, give a written notice to the Contracting Officer of (1) subsurface or latent physical conditions at the site which differ materially from those indicated in this contract, or (2) unknown physical conditions at the site, of an unusual nature, which differ materially from those ordinarily encountered and generally recognized as inhering in work of the character provided for in the contract.

(b) The Contracting Officer shall investigate the site conditions promptly after receiving the notice. If the conditions do materially so differ and cause an increase or decrease in the Contractor’s cost of, or the time required for, performing any part of the work under this contract, whether or not changed as a result of the conditions, an equitable adjustment shall be made under this clause and the contract modified in writing accordingly.

(c) No request by the Contractor for an equitable adjustment to the contract under this clause shall be allowed, unless the Contractor has given the written notice required; provided, that the time prescribed in (a) above for giving written notice may be extended by the Contracting Officer.

(d) No request by the Contractor for an equitable adjustment to the contract for differing site conditions shall be allowed if made after final payment under this contract.

Contracts predating the 1950s often failed to include any information regarding subsurface conditions.3 Because of this, contractors were at financial risk and frequently added contingencies to bids to cover the risk. To reduce the extent to which contingencies were priced in the bid, the government incorporated into the contract subsurface conditions that were expected to be encountered. However, representing subsurface conditions gave rise to liability for incorrect data. Use of a DSC clause attempts to resolve this problem and to minimize the “gambling” aspect of bidding underground work. The use has also resulted in lower prices to the owner.

2.2 SIMPLE CLAUSES

A simple, representative clause may be as innocuous as the following:

The tenderer shall be deemed to have examined the drawings, specifications, schedules and general conditions of the contract carefully and also to have fully informed him/herself as to the site and local conditions affecting the carrying out of the contract.

In other cases, the representation may be more restrictive, such as the following:

It is hereby declared and agreed by the contractor that this agreement has been entered into by (him) on (his) own knowledge respecting the nature and conformation of the ground on which the work is to be done; the location, character, quality and quantities of the material to be removed; the character of the equipment and facilities needed; the general and local conditions and all other matters which can affect the work under this agreement, and the contractor does not rely upon any information given or statement made to (him) in relation to the work by the owner.

2.3 AIA CLAUSE

The standard clause “Claims for Concealed or Unknown Conditions” contained in AIA Document A201, General Conditions of the Contract for Construction, states as follows:4

If conditions are encountered at the site which are (1) subsurface or otherwise concealed physical conditions which differ materially from those indicated in the Contract Documents or (2) unknown physical conditions of an unusual nature, which differ materially from those ordinarily found to exist and generally recognized as inherent in construction activities of the character provided for in the Contract Documents, then notice by the observing party shall be given to the other party promptly before conditions are disturbed and in no event later than 21 days after first observance of the conditions. The Architect will promptly investigate such conditions and, if they differ materially and cause an increase or decrease in the Contractor’s cost of, or time required for, performance of any part of the Work, will recommend an equitable adjustment in the Contract Sum or Contract Time, or both. If the Architect determines that the conditions at the site are not materially different from those indicated in the Contract Documents and that no change in the terms of the Contract is justified, the Architect shall so notify the Owner and Contractor in writing, stating the reasons. Claims by either party in opposition to such determination must be made within 21 days after the Architect has given notice of the decision. If the Owner and Contractor cannot agree on an adjustment in the Contract Sum or Contract Time, the adjustment shall be referred to the Architect for initial determination, subject to further proceedings pursuant to Paragraph 4.4 [Resolution of Claims and Disputes].

2.4 AGC CLAUSE

The Associated General Contractors of America’s (AGC) standard DSCs clauses contained in AGC Document415 – Standard Form of Design-Build Agreement and General Conditions Between Owner and Contractor (Lump Sum) – state:5

7.1.4 Should concealed conditions encountered in the performance of the Work below the surface of the ground or should concealed or unknown conditions in an existing structure be at variance with the conditions indicated by the Drawings, Specifications, or Owner‑furnished information or should unknown physical conditions below the surface of the ground or should concealed or unknown conditions in an existing structure of an unusual nature, differing materially from those ordinarily encountered and generally recognized as inherent in work of the character provided for in this Agreement, be encountered, the Lump Sum and the Contract Time Schedule shall be equitably adjusted by Change Order upon claim by either party made within a reasonable time after the first observance of the conditions.

7.2.1 If the Contractor wishes to make a claim for an increase in the Lump Sum or an extension in the Contract Time Schedule he shall give the Owner written notice thereof within a reasonable time after the occurrence of the event giving rise to such claim. This notice shall be given by the Contractor before proceeding to execute the Work, except in an emergency endangering life or property in which case the Contractor shall act, at his discretion, to prevent threatened damage, injury or loss. Claims arising from delay shall be made within a reasonable time after the delay. Increases based upon design and estimating costs with respect to possible changes requested by the Owner, shall be made within a reasonable time after the decision is made not to proceed with the change. No such claim shall be valid unless so made. If the Owner and the Contractor cannot agree on the amount of the adjustment in the Lump Sum, and the Contract Time Schedule, it shall be determined pursuant to the provisions of Article 13 [Arbitration]. Any change in the Lump Sum or Contract Time Schedule resulting from such claim shall be authorized by Change Order.

2.5 EJCDC CLAUSE

The Engineers’ Joint Contract Documents Committee’s (EJCDC) standard DSCs clauses – “Subsurface and Physical Conditions” and “Physical Conditions –Underground Facilities”– that appear in EJCDC Document 19 10-8, Standard General Conditions of the Construction Contract, provide as follows:6

4.2 Subsurface and Physical Conditions:

4.2.1. Reports and Drawings: Reference is made to the Supplementary Conditions for identification of:

4.2.1.1. Subsurface Conditions: Those reports of explorations and tests of subsurface conditions at or contiguous to the site that have been utilized by ENGINEER in preparing the Contract Documents; and

4.2.1.2. Physical conditions: Those drawings of physical conditions in or relating to existing surface or subsurface structures at or contiguous to the site (except Underground Facilities) that have been utilized by ENGINEER in preparing the Contract Documents.

4.2.2. Limited Reliance by CONTRACTOR Authorized: Technical Data: CONTRACTOR may rely upon the general accuracy of the “technical data” contained in such reports and drawings, but such reports and drawings are not Contract Documents. Such “technical data” is identified in the Supplementary Conditions. Except for such reliance on such “technical data,” CONTRACTOR may not rely upon or make any claim against OWNER, ENGINEER or any of ENGINEER’s Consultants with respect to:

4.2.2.1. the completeness of such reports and drawings for CONTRACTOR’s purposes, including, but not limited to, any aspects of the means, methods, techniques, sequences and procedures of construction to be employed by CONTRACTOR and safety precautions and programs incident thereto, or

4.2.2.2. other data, interpretations, opinions and information contained in such reports or shown or indicated in such drawings, or

4.2.2.3. any CONTRACTOR interpretation of or conclusion drawn from any “technical data” or any such data, interpretations, opinions or information.

4.2.3. Notice of Differing Subsurface or Physical Conditions: If CONTRACTOR believes that any subsurface or physical condition at or contiguous to the site that is uncovered or revealed either:

4.2.3.1 is of such a nature as to establish that any “technical data” on which CONTRACTOR is entitled to rely as provided in paragraphs 4.2.1 and 4.2.2 is materially inaccurate, or

4.2.3.2 is of such a nature as to require a change in the Contract Documents, or

4.2.3.3 differs materially from that shown or indicated in the Contract Documents, or

4.2.3.4 is of an unusual nature, and differs materially from conditions ordinarily encountered and generally recognized as inherent in work of the character provided for in the Contract Documents; then CONTRACTOR shall, promptly after becoming aware thereof and before further disturbing conditions affected thereby or performing any work in connection therewith (except in an emergency as permitted by paragraph 6.23), notify OWNER and ENGINEER in writing about such condition. CONTRACTOR shall not further disturb such conditions or perform any Work in connection therewith (except as aforesaid) until receipt of written order to do so.

4.3 Physical Conditions – Underground Facilities:

4.3.1. Shown or Indicated: The information and data shown or indicated in the Contract Documents with respect to existing Underground Facilities at or contiguous to the site is based on information and data furnished to OWNER or ENGINEER by the owners of such Underground Facilities or by others. Unless it is otherwise expressly provided in the Supplementary Conditions:

4.3.1.1. OWNER and ENGINEER shall not be responsible for the accuracy or completeness of any such information or data; and

4.3.1.2. The cost of all of the following will be included in the Contract Price and CONTRACTOR shall have full responsibility for: (i) reviewing and checking all such information and data, (ii) locating all Underground Facilities shown or indicated in the Contract Documents, (iii) coordination of the Work with the owners of such Underground Facilities during construction, and (iv) the safety and protection of all such Underground Facilities as provided in paragraph 6.20 and repairing any damage thereto resulting from the Work.

4.3.2. Not Shown or Indicated: If an Underground Facility is uncovered or revealed at or contiguous to the site which was not shown or indicated in the Contract Documents CONTRACTOR shall, promptly after becoming aware thereof and before further disturbing conditions affected thereby or performing any Work in connection therewith (except in an emergency as required by paragraph 6.23), identify the owner of such Underground Facility and give written notice to that owner and to OWNER and ENGINEER. ENGINEER will promptly review the Underground Facility and determine the extent, if any, to which a change is required in the Contract Documents to reflect and document the consequences of the existence of the Underground Facility. If ENGINEER concludes that a change in the Contract Documents is required, a Work Change Directive or a Change Order will be issued as provided in Article 10 to reflect and document such consequences. During such time, CONTRACTOR shall be responsible for the safety and protection of such Underground Facility as provided in paragraph 6.20. CONTRACTOR shall be allowed an increase in the Contract Price or an extension of the Contract Times, or both, to the extent that they are attributable to the existence of any Underground Facility that was not shown or indicated in the Contract Documents and that CONTRACTOR did not know of and could not reasonably have been expected to be aware of or to have anticipated. If OWNER and CONTRACTOR are unable to agree on entitlement to or the amount or length of any such adjustment in Contract Price or Contract Times, CONTRACTOR may make a claim therefor as provided in Articles 11 and 12. However, OWNER, ENGINEER and ENGINEER’S Consultants shall not be liable to CONTRACTOR for any claims, costs, losses or damages incurred or sustained by CONTRACTOR on or in connection with any other project or anticipated project.

2.6 GENERAL CONTRACTOR/SUBCONTRACTOR CLAUSE FOR CONSTRUCTION OF A CHEMICAL PLANT

An example of a “Site Conditions” clause required by a general contractor in a subcontractor’s contract follows:

The Subcontractor represents that it has independently examined the site of the work, has investigated and considered all of the conditions affecting execution of the work, is fully capable of performing the work under said conditions, and agrees to waive all claims against the Contractor on account of any such conditions. Subcontractor acknowledges that it is aware of the potential for ammonia fumes to interrupt job site activities periodically.

2.7 OWNER CLAUSE FOR CONSTRUCTION OF A HEAVY RAIL TRANSPORTATION PROJECT

A DSC clause used by an owner of a Heavy Rail Transportation project states the following:

Differing Site Conditions. The Contractor shall promptly, and before the conditions are disturbed, notify the Engineer, in writing in accordance with Article GC9.4, of:

(a) Subsurface or latent physical conditions at the site which differ from those indicated in the Contract Documents;

(b) Unknown physical conditions at the site, of an unusual nature, which differ materially from those ordinarily encountered and generally recognized as inherent in Work of the character provided in the Contract;

(c) Material deviations from dimensions, tolerances, conditions or locations of facilities indicated; or

(d) Material that the Contractor believes may be material that is hazardous waste, as defined in section 25117 of the State Health and Safety Code, that is required to be removed to a Class I, Class II or Class III disposal site in accordance with provisions of existing law.

Investigation and Notice. The Engineer will promptly investigate such conditions, and if the Engineer finds that they do so materially differ, or do involve such hazardous waste, and cause an increase or decrease in the Contractor’s cost of, or time required for, performance of the particular portion of the Work in question, an adjustment will be made in accordance with the change provisions in Article GS4.2. If the Contractor fails to give notice to the conditions being disturbed, the Contractor waives any claim for extra time or extra compensation in any manner arising out of such conditions.

Work to Proceed. In the event that a dispute arises between the District and the Contractor whether the conditions materially differ, or involve hazardous waste, or cause an increase or decrease in the Contractor’s cost of, or time required for, performance of any part of the work, the Contractor shall not be excused from any scheduled completion date provided for by the Contract, but shall proceed with all work to be performed under the Contract and shall strictly comply with the notice and other claims procedures set forth in Article GC9.4.

2.8 SUBCONTRACT AGREEMENT CLAUSE

A DSC clause found in a subcontract agreement states the following:

If conditions are encountered at the construction site which are (1) subsurface or otherwise concealed physical conditions (including conditions concealed within existing structures) which differ materially from those indicated in the Contract Documents or (2) unknown physical conditions of an unusual nature which differ materially from those ordinarily found to exist and generally recognized as inherent in construction activities of the character provided for in the Contract Documents, the Subcontractor shall give the Contractor notice promptly before conditions are disturbed and in no event later than forty‑eight (48) hours after first observance of the conditions, or, if sooner, the date the Contractor is required to report the condition pursuant to the Contract Documents. The Subcontractor shall not be entitled to any increase in the Subcontract Price or damages by reason of any such conditions unless the owner is liable for and pays the same to the Contractor, nor shall the Subcontractor be entitled to an extension of the time for performance of the Subcontractor’s Work unless the Owner grants such extension for performance of the Subcontractor’s Work. The Contractor shall not be obligated to apply to the Owner for an increase in the Subcontract Price or for damages on behalf of the Subcontractor or for an extension of time under this Agreement unless such application is provided for by the Contract Documents, and Subcontractor, at its expense, does all things necessary in order to process such claim. The Contractor, upon receipt of any payment by the Owner, based upon such claim for the Subcontractor, will pay the same to the Subcontractor less its expenses. Except to the extent provided in this section, the Subcontractor waives the right to make any claims based on conditions encountered at the construction site.

2.9 FIDIC “CIVIL” CLAUSE

The Federation Internationale des Ingenieurs Conseils (FIDIC), commonly known as the International Federation of Consulting Engineers, provides two standard form contracts – the Conditions of Contract for Works of Civil Engineering Construction and the Conditions of Contract for Electrical and Mechanical Works. Although the wording of the DSCs clauses included in the two documents is different, the intent of the two clauses is apparently the same. Therefore, only the “Sufficiency of Tender” clause and “Adverse Physical Obstructions or Conditions” clause contained in the FIDIC Conditions of Contract for Works of Civil Engineering Construction are quoted below:7

12.1 The Contractor shall be deemed to have satisfied himself as to the correctness and sufficiency of the Tender and of the rates and prices stated in the Bill of Quantities, all of which shall, except insofar as it is otherwise provided in the Contract, cover all his obligations under the Contract (including those in respect of the supply of goods, materials, Plant or services or of contingencies for which there is a Provisional Sum) and all matters and things necessary for the proper execution and completion of the Works and the remedying of any defects therein.

12.2 If, however, during the execution of the Works the Contractor encounters physical obstructions or physical conditions, other than climatic conditions on the Site, which obstructions or conditions were, in his opinion, not foreseeable by an experienced contractor, the Contractor shall forthwith give notice thereof to the Engineer, with a copy to the Employer. On receipt of such notice, the Engineer shall, if in his opinion such obstructions or conditions could not have been reasonably foreseen by an experienced contractor, after due consultation with the Employer and Contractor determine:

(a) any extension of time to which the Contractor is entitled under Clause 44, and

(b) the amount of any costs which may have been incurred by the Contractor by reason of such obstructions or conditions having been encountered, which shall be added to the Contract Price, and shall notify the Contractor accordingly, with a copy to the Employer. Such determination shall take account of any instruction which the Engineer may issue to the Contractor in connection therewith, and any proper and reasonable measures acceptable to the Engineer which the Contractor may take in the absence of specific instructions from the Engineer.

2.10 FIDIC EPC TURNKEY PROJECT CLAUSE, 1998 TEST EDITION

In 1998, FIDIC issued a test edition for Conditions of Contract for EPC Turnkey Projects. That contract did not contain a DSC Clause per se, but instead included the following:

4.10 Site Data. The Employer shall have made available to the Contractor for his information, prior to the Base Date, all relevant data in the Employer’s possession on hydrological and sub-surface conditions at the site, including environmental aspects. The Contractor shall be responsible for verifying and interpreting all such data.

4.12 Unforeseeable Difficulties. The Contractor shall be deemed to have obtained all necessary information as to risks, contingencies, and other circumstances which may influence or affect the Works. By signing the Contract, the Contractor accepts responsibility for having foreseen all difficulties and costs of successfully completing the Works. The Contract Price shall not be adjusted to take account of any unforeseen difficulties or costs, except as otherwise stated in the Contract.

2.11 COMPARISON OF THE CLAUSES

AIA Document A201, AGC Document 415, and EJCDC Document 19 10-8, in general, adopt the basic provisions of the FAR differing site conditions clause. The clauses provide for recovery where physical conditions encountered differ materially from what is indicated in the contract documents and where unknown physical conditions of an unusual nature are encountered that differ materially from those generally recognized and ordinarily found to exist. In addition, the clauses provide for an adjustment of the contract price and schedule.

These clauses each require that notice be given after encountering a DSC but before the condition is disturbed. They differ somewhat, however, in that the FAR, AGC, and EJCDC clauses put the burden of notice (written) on the contractor, while the AIA clause states that the observing party shall give notice. The AGC’s Document 415 provides for an increase or decrease in the contract price and schedule upon a claim by either party (owner or contractor). However, the clause does not impose a notice requirement on the owner, whereas it does on the contractor. The clauses also differ regarding the timeliness of notice. The FAR DSCs clause and EJCDC Document 19 10‑8 state that the contractor shall give notice “promptly;” AIA Document A201 further defines “promptly” to be no later than 21 days after first observance; and AGC Document 415 states that notice is to be given within a reasonable time after the occurrence.

Although EJCDC Document 19 10‑8 generally adopts the basic provisions of the FAR DSCs clause, the EJCDC clauses are more detailed than the other standard form clauses. Document 19 10‑8 distinguishes between subsurface and physical conditions in general and physical conditions in the form of underground facilities in particular. Clause 4.2 limits the contractor’s reliance to the accuracy of technical data – the contractor may not rely on or make claims against the owner based on non-technical data, interpretations, or opinions contained in reports or shown or indicated on drawings. In addition, Clause 4.3 of Document 19 10‑8 specifically denies any owner responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of any information or data with respect to existing underground facilities that are shown or indicated in the contract documents. Moreover, the clause only provides a price/time remedy to the contractor when an underground facility is uncovered or revealed that was not shown or indicated in the contract documents.

Clause 4.3 further denies the owner’s liability for any claims, costs, losses, or damages incurred by the contractor on any other project or anticipated project.

The General Contractor/Subcontractor Clause for Construction of a Chemical Plant specifically alerts the subcontractor about the presence of ammonia. While this is not a physical condition, the general contractor has taken the precaution of notifying the subcontractor of this condition to prevent any claims due to disruptions from gas releases in an existing plant.

The differing site conditions clause used by the owner for Construction of a Heavy Rail Transportation Project also identifies, within the DSC clause, the need for the contractor to provide notice if it finds a condition of hazardous waste or if it finds material deviations from dimensions, tolerances, conditions or locations of the facilities indicated in the Contract Documents.

The subcontract agreement clause puts the added risk that the subcontractor will not be paid, or its contract completion schedule will not be extended, unless the contractor first receives such adjustments and the subcontractor prepares a fully supported claim for the conditions encountered.

FIDIC’s Civil Clause 12, like the FAR DSCs clause, requires the contractor to provide timely notice when encountering a DSC. It also provides for both a cost and a time adjustment to the contract when encountering a DSC. Unlike the FAR DSCs clause, which requires the contractor to prove either that the condition encountered differs materially from the conditions indicated in the contract documents or that the conditions encountered were of an unusual nature and that they differ materially from the conditions generally recognized and ordinarily found to exist at the site, FIDIC’s DSCs clause only requires the contractor to prove that the physical obstructions or physical conditions encountered (excluding climatic conditions on the site) were not foreseeable by an experienced contractor. FIDIC’s DSCs clause potentially provides the contractor with more opportunities for recovery when a DSC is encountered.

FIDIC’s EPC Turnkey Contract Clause is a disclaimer rather than a basis for additional time and costs for changed conditions.

3. DIFFERING SITE CONDITIONS – TYPE I, TYPE II AND TYPE III CONDITIONS

Differing site conditions are often classified as either Type I, Type II, or Type III.

3.1 TYPE I CONDITIONS

A Type I DSC is generally defined as one in which actual physical (subsurface or latent) conditions encountered at the site differ materially from the conditions represented in the contract documents.8

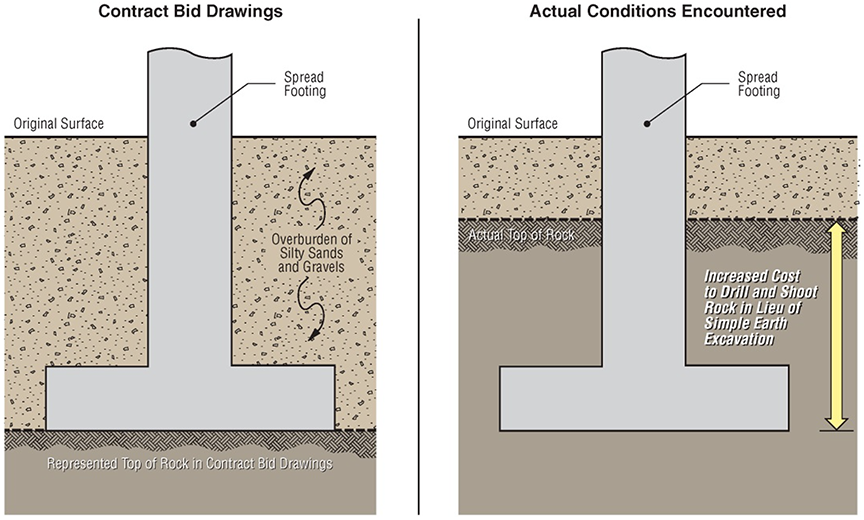

For example, see Figure 1 below. Each component of the Type I DSC must be established because the contractor bears the burden of proving entitlement.

Figure 1

Example of Type I Differing Site Condition (DSC)

To support its DSCs claim, the contractor must establish that: 1) the conditions encountered were physical, 2) the conditions were sub‑surface or latent, 3) they were encountered at the site, 4) there was a material difference between the conditions encountered and the conditions indicated in the contract,9,10 5) it relied on the information presented in the contract and did not fail to question the owner regarding ambiguities during the solicitation phase,11 6) the actual conditions encountered were unknown, 7) as a result of this reliance and the DSC encountered, the contractor’s cost of performance was increased, and 8) the contractor provided proper notice to the owner.12

(1) Physical Condition – The DSC must be a physical condition, as opposed to an economic,13 governmental,14 or political15 condition. However, natural (physical) conditions such as acts of God – infestations of stinging insects,16 excessive heat,17 highly damp ground cover,18 abnormal rainfall,19 rough seas,20 strong winds,21 hurricanes,22 severe temperatures or frozen ground,23 or flooding24 – by themselves do not constitute a DSC. Although an act of God by itself does not constitute a DSC, when an abnormal weather condition interacts with a latent adverse physical condition at the site, such interaction may create a site condition that is compensable as a DSC.25 For example, a landslide triggered by an unusually heavy rainfall, but incident to an undisclosed subsurface soil condition, may qualify as a DSC.26 The physical condition, in addition to being a natural condition, may also be an artificial or man‑made condition – such as underground electric power lines,27 sewer lines,28 or gas pipelines29 – that is unexpectedly encountered at the site.

(2) Subsurface or Latent Condition – In addition to being a physical condition, the DSC must also be subsurface or latent. The majority of DSC claims involve a change in some aspect (physical or mechanical properties,30 behavioral characteristics,31 quantities,32 etc.) of the anticipated subsurface material or structure (soil,33,34 rock,35 water,36 artificial or man‑made obstructions,37 etc.). A latent condition, on the other hand, need not be a subsurface condition. It may be above, at, or below the surface and is any physical condition (dormant, concealed, or hidden) unforeseeable to a reasonable and prudent contractor.38 Examples of latent conditions include ground contour elevations,39 undisclosed concrete piles,40 the thickness of a concrete floor,41 thickness of steel plate to be drilled,42 lead paint to be removed,43 significantly incorrect dimensions,44 depth of underwater clearance,45 condition of shower floor drains to be replaced,46 unexpected asbestos to be removed,47 the existence of electrical/ telephone lines,48 an additional layer of roofing,49 the existence of a subfloor,50 and the instability of soils forming an embankment.51

(3) Encountered At The Site – A DSC must be encountered at the site of the work. Generally, the site includes any area designated in the contract documents or any other areas where the contractor is directed by the owner to perform the work.52 This may also include an off‑site borrow or disposal site if the contractor is directed to obtain or dispose of materials off the site.53

(4) Material Difference and Contract Representations – Another component of a Type I DSC is that the physical condition encountered must be materially different from the condition indicated in the contract documents. A material difference is a substantial variance from what a reasonably prudent contractor would have expected to encounter based on its review of the contract documents.54 Redesign of some portion of the work,55 a change in the contractor’s planned method of construction, or a need to use a different size or type of equipment to accommodate the changed condition may in itself be sufficient to prove that a materially differing site condition was encountered.56 Contract documents may include the owner’s bid documents,57 the contractor’s bid submittal,58 the contract,59 general and special conditions,60 specifications,61 drawings and details,62 soil boring logs,63 site photographs,64 and written responses to questions.65 An interpretation of the conditions indicated in the contract documents will be made from the perspective of a reasonably prudent and experienced contractor and may include express contractual statements66 as well as implicit representations.67 However, if the contract expressly states that the site information as presented is incomplete, inaccurate, an estimate, or not part of the contract, recovery for a DSC may be limited or denied in its entirety.68

In addition, the contractor should be aware that the contract documents may be considered silent, at least in part, relative to subsurface conditions even if soil boring information is provided in the contract documents.69 If the contract documents are silent about subsurface conditions, a Type I DSC does not exist.70 Therefore, it is extremely important for the contractor to ensure that any data it relies on to prepare its bid are, in fact, part of the contract documents. In addition, the contractor should be aware of the order of precedence as stated in the contract regarding relevant data and any applicable (remedy granting and disclaimer) clauses.71

(5) Contractor Reliance – For a contractor to effectively establish that it was damaged by a DSC, the contractor must show that it relied on the subsurface conditions indicated in the contract documents to develop its bid price.72 In addition, the contractor must show that it was entitled to rely on the conditions indicated in the contract documents.73 The contractor’s actual or constructive knowledge of the conditions encountered, failure to review the data provided,74 or execution of a release agreement with the owner75 may negate its entitlement to recover for a DSC.

(6) Conditions Encountered Were Unknown – The contractor must also establish that the actual conditions encountered were unknown prior to submission of its bid. The contractor must demonstrate that the conditions encountered were not ascertainable by a review of the contract documents76 or a reasonable pre-bid site inspection,77 and that it was not aware of actual conditions as a result of its previous work experience78 or actual or constructive knowledge of site conditions in the area.79 The measure of what constitutes a reasonable site inspection will vary in every case, but where the conditions encountered would have been revealed by an adequate examination of the site and all other data available to bidders, the contractor that fails to make such a pre-bid investigation cannot expect to be afforded relief on the ground that it has encountered changed conditions.80

In this same regard, in making a site investigation, the contractor is only charged with the knowledge that a reasonably intelligent and experienced contractor would acquire from such an investigation and are not necessarily expected to reach the same conclusions that a geologist or other specialized expert might formulate from the same data.81 Also, the contractor is not obligated to seek out experts to determine the validity of the contract indications.82 In addition, relief under a DSCs clause will not be precluded where it is shown that the contractor was denied the chance to make a meaningful site investigation before bidding,83 or that a reasonable site investigation would not have revealed the condition.84

(7) Cost of Performance Increased – The contractor must also show that as a result of its reliance on the conditions indicated in the contract documents and the actual differing site conditions encountered, the contractor’s cost of performing the work increased.85 The contractor must establish the causal link between the contract representation, the actual conditions encountered, and its increased costs.86

(8) Notice – Finally, the contractor is normally obligated to provide written notice to the owner if it encounters a DSC but before the condition is disturbed.87 The contractor must give notice only of the existence of the condition; it need not give notice that overcoming the condition will entail additional costs.88

This notice requirement may be waived by the courts if the owner has not been prejudiced by the contractor’s failure to notify.89 Testing for prejudice considers four factors: the owner’s knowledge of the condition,90 the criticality of the condition,91 verification by the owner of the existence of the condition,92 and whether the owner could have reduced the cost incurred by the contractor to overcome the condition if the contractor had given prompt notice.93 Conversely, the contractor’s failure to provide notice may be viewed as an indication that it did not believe that it encountered a materially differing site condition.94 Therefore, the contractor’s contemporaneous actions may significantly impact the outcome of a DSC claim.

3.2 TYPE II CONDITIONS

A Type II DSC occurs when actual physical conditions encountered at the site differ materially from the conditions normally encountered and generally recognized to exist, given the nature and locale of the work. As previously stated, the major difference between a Type I and a Type II DSC is that, in a Type II DSC, the owner has not made any substantive representations or indications in the contract documents relative to anticipated or expected site conditions. Since the contractor cannot compare actual conditions to the contract documents, the contractor’s burden of proving a Type II DSC is significantly increased.95

In addition to the components previously identified that must be established to prove entitlement for a Type I DSC (except, of course, that the conditions are not “represented in the contract documents”), in a Type II DSC claim the contractor has the added burden of proving (1) what conditions are recognized and usual at the site, and (2) that the actual conditions encountered at the site were unusual.

(1) Recognized & Usual Condition – The contractor must establish what physical conditions would have been reasonably expected (recognized and usual) at the jobsite, given the nature and locale of the work.96 Establishing these reasonably expected physical conditions is based on a review of the contract documents, a pre-bid site investigation, and the knowledge of a prudent and experienced contractor.97

(2) Actual Conditions Encountered Were Unusual – In addition to establishing what the recognized and usual conditions at the site are, the contractor also must show that the actual physical conditions it encountered were unusual.98 Type II DSC claims have succeeded where there was (a) an anomaly to the site’s geographic area,99 (b) an obstruction that was located in a strange and uncommon location,100 (c) a condition not normally found in other similar structures,101 (d) a condition known to the contractor but the magnitude of the condition’s effect on the performance of the contract was more than would normally be expected,102 and (e) an unexplained phenomenon.103 Specific examples include highly corrosive groundwater,104 excessive hydrostatic pressure,105 jet fuel in manholes,106 presence of caked material in heating ducts,107 an oily substance that prevented adherence of a PVC coating,108 and the failure of rock to fracture in the manner anticipated.109

Type II claims have been denied, when one of the following conditions has been present: (1) the condition was common to buildings or structures built during a particular era even though the contractor was not accustomed to the existence of the condition;110 (2) the condition was subsurface water and the site was located near a large body of water;111 (3) the condition was an obstruction in a customary location;112 (4) the contractor had experienced the condition on similar projects;113 (5) the condition should have been known from a review of the boring logs,114 and (6) the condition was normal for the geographic area.115

3.3 TYPE III CONDITIONS

A Type III DSC clause typically assigns the risk of handling unanticipated hazardous materials to the owner. An increasing trend in the public rail transportation industry is to identify in the contract and bidding documents the increased potential for encountering hazardous materials during site dewatering and excavation. Portions of light, heavy, and commuter rail lines are often situated on former freight lines where tank car leakages have occurred over many years and creosoted track ties were used with associated creosote leachate. The developing trend among agencies is:

- Define the types of hazardous materials and identify the certified disposal sites to be used for disposal;

- Define the labeling and conditions for trucking and or packaging for transportation to the disposal site;

- The contractor would be required to have onsite inspection and testing services to identify the specific truckload assignment for disposal;

- A unit bid price would be included in the contract for each month of inspection and lab utilization; and

- A set of unit price items, one for each disposal type, on a tonnage basis, would be bid and contracted.

The above practices greatly reduce the potential for claims for Type III differing site conditions and may be limited to the types of hazardous waste materials not accepted by regional certified disposal sites. A similar procedure could be established for contaminated water, where the construction contractor would provide for a holding tank and onsite treatment facilities.

A sample DSC clause for Type I, II, and III conditions is provided below:

ARTICLE 8 – DIFFERING SITE CONDITIONS

8.1 (a) The Contractor shall promptly and before the conditions are disturbed (but in any event no later than 5 days after first discovery of such conditions), give a written notice to the Owner of:

1. subsurface or latent physical conditions at the site which differ materially from those indicated in this Agreement, or

2. unknown physical conditions at the site, of an unusual nature, which differ materially from those ordinarily encountered and generally recognized as inhering in work of the character provided for in this Agreement, or

3. materials that the Contractor believes may be hazardous.

(b) The Owner shall investigate the site conditions promptly after receiving the notice. If the conditions do materially so differ and cause an increase or decrease in the Contractor’s cost of, or the time required for, performing any part of the work under this Agreement, whether or not changed as a result of the conditions, an equitable adjustment shall be made under this clause and this Agreement modified in writing accordingly.

(c) No request by the Contractor for an equitable adjustment to this Agreement under this clause shall be allowed unless the Contractor has given the written notice required; provided, that the time prescribed in (a) above for giving written notice may be extended by the Owner.

4. THE CONTRACT ABSENT A DIFFERING SITE CONDITIONS CLAUSE

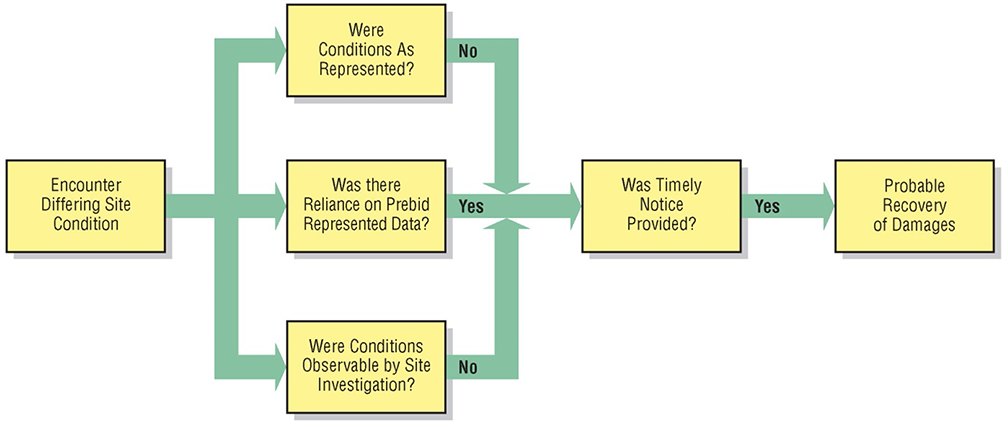

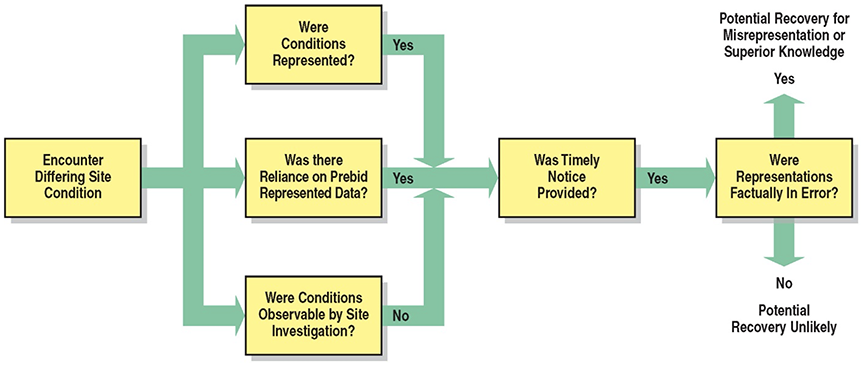

Absent a DSCs clause in the contract, the contractor’s only avenue to recovery for encountering a DSC is under the principles or theories of common law.116 Figures 2 and 3 present recovery paths with and without a DSC clause in the contract. Several common law theories exist that may provide the contractor a basis for recovery from a DSC. These include misrepresentation, fraud, breach of contract, breach of warranty, mutual mistake, superior knowledge, and unjust enrichment.

Figure 2

Liability/Notice Flowchart for DSC Contract Containing a DSC Clause

Figure 3

Liability/Notice Flowchart for DSC Contract Absent a DSC Clause

4.1 MISREPRESENTATION

The contractor may be able to recover the extra costs associated with adverse subsurface conditions if it can show that the data furnished by the owner misrepresented the actual conditions encountered.117 The key elements required to prove misrepresentation include (1) the contractor justifiably relied on the information represented in the contract documents, (2) the actual conditions encountered differed materially from conditions indicated in the contract documents, (3) the owner erroneously concealed information that was material to the contractor’s performance, and (4) the contractor incurred increased costs of performance due to the conditions encountered.118

To establish Item 1 above that the contractor’s reliance on the information presented in the contract was justifiable, three factors are normally considered by the courts. First, the wording of the representation regarding subsurface conditions included in the contract will be reviewed to determine whether it is a positive or a suggestive representation of site conditions. The more definitive (positive) the representation, the more likely the courts will find the contractor justifiably relied on the data furnished.119

Second, the disclaimer language (assuming the owner included a disclaimer in the contract) will be reviewed to determine whether the wording is general or specific. The more specific the wording, the less likely the court will find justifiable reliance.120 In certain instances, the courts have held that positive representations regarding subsurface data may be relied on despite the presence of a clause disclaiming any liability for the accuracy of those representations.121

The third factor that will be considered to determine whether the contractor’s reliance was justified is whether it conducted a pre-bid site inspection. The courts will determine if a reasonable site investigation would have revealed the DSCs that were actually encountered. If not, the contractor will most likely be relieved of its contractual responsibility to inspect the site and, therefore, will be allowed to recover its increased costs of performance.122

4.2 FRAUD

Fraud and misrepresentation are two related legal theories; the key difference is that, to prove fraud, the contractor must show that errors or inaccuracies were intentionally included with the subsurface data for the purpose of obtaining a lower bid. Under common law, the contractor bears the burden of showing an express statement in the contract documents that demonstrates that the owner intended to mislead the contractor. However, some courts have relaxed this common law requirement. In those instances, if the contractor can prove that the owner knew one thing and represented another, the courts have provided the connecting factor and inferred the necessary improper intent.123

4.3 BREACH OF CONTRACT OR WARRANTY

Another potential avenue for recovery for the contractor is to allege a breach of contract based on misrepresentation or fraud. If the contractor can prove that the owner concealed information about site conditions, it may be successful on a breach of contract claim.124

Another frequently used theory to recover for a DSC is that the owner breached its warranty (implied or express) that the representations in the contract documents are accurate and that the plans and specifications are adequate to produce a satisfactory project that is suitable for its intended use.125 However, warranties are not imputed to owners who do not provide plans or specifications or do not give a description of the site. Further, owners are not liable for a breach of warranty if they do not have knowledge of latent defects and do not contribute to the contractor’s mistaken belief.126

Any breach of warranty action must be based on a positive or affirmative representation by the owner rather than one that is merely suggestive.127 In addition, the contractor must demonstrate its reliance on, and compliance with, the owner’s defective contract documents in bid preparation and work performance.128

4.4 OTHER THEORIES

Under a mutual mistake theory, if a contractor can show that, at the time of contract formation, the contractor and the owner made a mistake as to a factual condition that goes to the “very essence” of the contract, the contractor may be successful in having the contract rescinded and having its actual costs paid.129

The courts have also established that, if an owner possesses special knowledge that is vital to the performance of a contract, but the contractor is ignorant of that information and the information is not reasonably available to the contractor, then the owner has a duty to disclose its superior knowledge.130 To advance a claim based on superior knowledge, the contractor must establish the following: (a) the owner failed to disclose facts that it had a duty to disclose, (b) the owner knew that the contractor would act on the false or incomplete information provided, (c) the contractor relied on the owner to disclose all pertinent information, and (d) the contractor’s cost of performance increased as a result of not having the superior knowledge.131

Usually, the owner has a duty to disclose information without a specific request from the contractor.132 However, some decisions have held that the owner is not under any duty to disclose all information in its possession unless the contractor makes a specific request for all available information.133

To advance a claim for unjust enrichment for a differing site condition, the contractor must establish that (1) the work completed was not originally required by the contract and (2) the owner directed or agreed to have the work competed.134 Recovery for unjust enrichment is based on the concept that, if the contractor (not acting as a volunteer) provides services that are beyond the scope of work required by the contract, the owner will be unjustly enriched if the contractor does not receive a fair value for the extra work performed.

5. OWNER DEFENSES

The primary defenses used by owners to defend against DSC claims are contract disclaimers and notice requirements. These defenses are discussed below.

5.1 CONTRACT DISCLAIMERS

As previously mentioned, in an effort to secure more realistic bids by eliminating contractor contingencies to cover unknown subsurface conditions, owners have become more willing to make positive representations as to expected subsurface conditions. However, owners have also tried to avoid liability for any deviations from those expected conditions. Owners attempt to avoid liability by including a “Site Investigation” clause in the contract, by disclaiming the accuracy of subsurface data, by requiring the contractor to sign a release before the owner will provide the subsurface data, and by not including a DSCs clause in the contract. As a result, a dichotomy is born within the contract. The owner provides data on subsurface conditions on which a contractor will likely rely, while, at the same time, the owner includes contract language to avoid liability should the information prove incorrect.135

An example agreement contains the following disclaimer:

ARTICLE 7 – INSPECTION OF SITE, CONDITIONS, AND PLANS

7.1 Contractor represents that it has carefully examined and inspected all matters, conditions and circumstances affecting Contractor’s proper and timely performance of the Work, including, without limitation, (i) the terms, conditions and obligations of this Agreement, (ii) the extent, nature and quality of the Work, (iii) the services, labor, materials and equipment necessary for the proper performance of the Work, (iv) the location and condition of the Site and its surroundings, and (v) the conditions under which the Work will be performed. Furthermore, Contractor represents that it has obtained all information available in connection therewith, and has fully examined and informed itself and its Subcontractors of all general, local and physical conditions which may affect its performance under this Agreement including, without limitation, all applicable laws, orders, codes, ordinances, and/or regulations, local labor requirements, prevailing wage rates, general working conditions in the area, ground and surface conditions, on-site security needs, access to and egress from the Site, disposal, handling and storage of all substances, materials and wastes, availability of housing, transportation laydown and the general topographic and geologic characteristics of the region. Contractor represents that it is fully aware of all existing conditions and has reviewed and acknowledges the results of all subsurface reports or tests, identified in or set forth in Exhibit E [any subsurface reports and/or information should be included in Exhibit E] hereto, and limitations including normal weather and climatic conditions, and all laws, ordinances, rules and regulations, Federal, State and local, affecting the performance of the Work. Contractor hereby waives any and all right to claim that conditions of the Site or other property in the vicinity give rise to or otherwise constitutes an excuse for delay or non-performance or the basis of a cost adjustment under this Agreement, except as provided in Article 8 of this Agreement.

7.2 Contractor represents that it has carefully studied in detail the job requirements and specifications provided in Exhibit E and all other documents and information furnished to it by Owner and that it is fully satisfied as to their correctness and adequacy for the proper and timely performance of the Work by Contractor.

7.3 Contractor recognizes that the Plant is to be constructed and operated in accordance with all local, state and federal environmental laws including those pertaining to water, air, solid waste, hazardous waste, and noise pollution. Contractor will comply with all such laws and with the rules, regulations and other requirements of the State of _________, the Federal Environmental Protection Agency, [modify as necessary for international contracts] and any and all other governmental authorities having jurisdiction over the environment or the relation of the Plant to the environment. Anything in this Paragraph 7.3 to the contrary notwithstanding, Contractor shall have the right to request a Change Order in order to comply with any environmental law, rule or regulations enacted, adopted or ratified subsequent to the date of this Agreement. The Contract Price and Schedule do not contemplate the discovery of any pre-existing hazardous materials at the Site. In the event any such materials are discovered, Contractor shall immediately notify Owner, Owner shall take such actions as appropriate and such discovery will be governed by Article 8 of this Agreement.

7.4 Having fully acquainted itself with the Work, the Site and its surroundings, and any risks in connection therewith, Contractor assumes full and complete responsibility for performing the Work for the compensation set forth in Exhibit B, Compensation, Payment and Taxes, and achieving Mechanical Completion by the Scheduled Mechanical Completion Date set forth in Exhibit C, Schedule of Completion. Contractor’s failure to carry out the activities set forth in Articles 7.1, 7.2 and 7.3 hereof shall not relieve Contractor of any of its obligations under this Agreement.

Disclaimers are less of a problem, however, in federal construction contracts because of the rule that, where an agency’s regulations require inclusion of a particular contract provision, that provision is automatically included by operation of law notwithstanding its absence from a particular contract.136 The effect of this rule, as applied to DSCs, is that the Federal government may not prevent the contractor’s recovery under the DSCs clause by including a disclaimer clause in the same contract.137

5.2 LACK OF TIMELY NOTICE

The most effective defense against a differing site conditions claim is that the contractor failed to provide proper notice to the owner. Contracts often contain a notice requirement, particularly with regard to DSCs. Contracts may also require that the DSC remain undisturbed until the owner can investigate. Failure to strictly adhere to these notice requirements can foreclose a contractor’s recovery for an otherwise valid differing site conditions claim.138 The notice requirement is necessary to afford the owner the opportunity to inspect the condition, modify or alter the design or performance requirements and, thereby, minimize or mitigate the effects of the DSC.

About the Authors

Richard J. Long, P.E., P.Eng., is Founder of Long International, Inc. Mr. Long has over 50 years of U.S. and international engineering, construction, and management consulting experience involving construction contract disputes analysis and resolution, arbitration and litigation support and expert testimony, project management, engineering and construction management, cost and schedule control, and process engineering. As an internationally recognized expert in the analysis and resolution of complex construction disputes for over 35 years, Mr. Long has served as the lead expert on over 300 projects having claims ranging in size from US$100,000 to over US$2 billion. He has presented and published numerous articles on the subjects of claims analysis, entitlement issues, CPM schedule and damages analyses, and claims prevention. Mr. Long earned a B.S. in Chemical Engineering from the University of Pittsburgh in 1970 and an M.S. in Chemical and Petroleum Refining Engineering from the Colorado School of Mines in 1974. Mr. Long is based in Littleton, Colorado and can be contacted at rlong@long-intl.com and (303) 972-2443.

Robert J. Lane was a Senior Principal with Long International and retired in 2021. He has over 40 years of experience working in or consulting for the engineering and construction industry and spent more than half of that time involved in the resolution of construction-related claims and disputes. Mr. Lane has expertise in project-related estimating, cost control and scheduling, retrospective schedule analysis, productivity analyses, and quantum/damages analyses. He has also worked in the areas of contract administration, claims management, and overall project and construction management. Mr. Lane has significant background in the application of the Primavera scheduling systems to develop and update project schedules and/or to retrospectively analyze the impact of various events to a project schedule, including evaluations of entitlement to time extensions, acceleration costs, liquidated damages, and delay-related costs. Mr. Lane earned a B.S. in Construction Engineering from Purdue University in 1973 and an M.S. in Business Management and Administration from Pepperdine University in 1983. For further information, please contact Long International’s corporate office at (303) 972-2443.

James E. Kelley, Jr., P.E., was a Senior Principal with Long International and retired in 2018. He has over 50 years of experience in the construction industry, both in field construction assignments and in consulting roles. Over the last 30 years, Mr. Kelley has developed substantial expertise on highway, tunneling, and bridge construction projects, including the determination and allocation of construction delay and impact damages, analysis of complex cause/effect relationships to determine of root causes of problems, and the interpretation of defective contractual terms and conditions. Mr. Kelley has assisted clients in over 375 engagements, including construction contractors and subcontractors, design professionals, private and public owners of construction, real estate developers, mining company owners/operators, manufacturers, insurance and surety companies, utilities, attorneys, and financial institutions. Mr. Kelley earned a B.S. in Civil Engineering from Purdue University in 1964. For further information, please contact Long International’s corporate office at (303) 972‑2443.

1 FAR 36.502.

2 FAR 52.236-2 (Apr. 1984). The clause was renamed in 1967 from “Changed Conditions” to “Differing Site Conditions,” Federal Procurement Regulation 1-7.602-4; Defense Acquisition Regulation 7-602.4. See generally Currie, Abernathy & Chambers, “Changed Conditions,” Construction Briefings No. 84-12 (Dec. 1984), 2 CBC 489.

3 ASBCA, 02-1 BCA ¶ 31,669 Kato Corporation; ASBCA No. 51513, November 30, 2001.

4 AIA Doc. A201, cl. 4.3.6 (1987).

5 AGC Doc. 415, cls. 7.1.4 and 7.2.1 (Feb. 1986).

6 EJCDC Doc. 19 10-8, clauses 4.2 and 4.3 (1990).

7 FIDIC, Conditions of Contract for Works of Civil Engineering Construction, clauses 12.1 and 12.2 (4th ed. 1987).

8 ASBCA, 00-1 BCA ¶ 30,726 Overstreet Electrical Company, Inc.; ASBCA Nos. 51655, 51823, January 7, 2000.

9 Ragonese v. U.S., 128 Ct. Cl. 156 (1954); S.T.G. Const. Co. v. U.S., 157 Ct. Cl. 409 (1962); Stock & Grove, Inc. v. U.S., 493 F.2d 629 (Ct. Cl. 1974); Foster Const. C.A. v. U.S., 193 Ct. Cl. 587 (1970).

10 ASBCA, 01-2 BCA ¶ 31,583 Wright Dredging Company, Inc.; ASBCA No. 5294, August 29, 2001.

11 ASBCA, 96-1 BCA ¶ 28,007 Tom Shaw Inc.; ASBCA Nos. 28596, 28720, 28872, 28873, 28874, 37290, September 29, 1995.

12 Brechan Enterprises, Inc. v. U.S., 12 Cl. Ct.545 (1987), 6 FPD ¶ 87,11 CC ¶ 284; EZ Const. Co., ASBCA 31506, 87-1 BCA ¶ 19679.

13 Hallman v. U.S., 80 F. Supp. 370 (Ct. Cl. 1948); Bateson-Stolte, Inc. v. U.S., 145 Ct. Cl. 387 (1959); Doll Painting Co., ASBCA 9305,64-1 BCA ¶ 4458; Wilkinson & Jenkins Const. Co., ENGBCA 2776, 67-1 BCA ¶ 6169; Cross Const. Co., ENGBCA 3676, 79-1 BCA ¶ 13707.

14 Ingalls Shipbldg. Co., Eng. C.&A. 569 (1954); George A. Rutherford Co., NASABCA 12, 62-1 BCA ¶ 3561; Datatronics Engrs., Inc., ASBCA 10284, 65-2 BCA ¶ 5147; Yarno & Assocs., ASBCA 10257, 67-1 BCA ¶ 6312; Koppers Co., ENGBCA 2699, 67-2 BCA ¶ 6532; Fort Sill Assocs., ASBCA 7482, 63-1 BCA ¶ 3869, affd., 183 Ct. Cl. 301 (1968); ABCO Builders, Inc., PODBCA 282,69-1 BCA ¶ 7434; Blake Const. Co., GSBCA 2577, 72-1 BCA ¶ 9456; Pullaro Contracting Co., AGBCA 279, 73-1 BCA ¦ 9937.

15 Keang Nam Enterprises, Ltd., ASBCA 13747,69-1 BCA ¶ 7705.

16 ENG BCA, 96-2 BCA ¶ 28,303, Midland Maintenance Inc.; ENG BCA No. 6084 April 25, 1996.

17 ASBCA, 12-2 BCA ¶ 35,088, Strand Hunt Construction, Inc.; ASBCA No. 55904, June 21, 2012.

18 EBCA, 97-2 BCA ¶ 29,207, Lamb Engineering & Construction Company; EBCA No. C-9304172, July 28, 1997.

19 George A. Fuller Co., ASBCA 8524, 62-1 BCA ¶ 3619; E. J. T. Const. Co., ASBCA 17425, 73-2 BCA ¶ 10050; Frank W. Miller Const. Co., ASBCA 22347, 78-1 BCA ¶ 13039; Reinhold Const., Inc., ASBCA 23770, 79-2 BCA ¶ 14123; Maintenance Engrs., ASBCA 23131, 81-2 BCA ¶ 15168; Praxis-Assurance Venture, ASBCA 24748, 81-1 BCA ¶ 15028, modified on other grounds, 83-1 BCA ¶ 16411.

20 Hardeman-Monier-Hutcherson v. U.S. (1972) 17 CCF ¶ 81,368, 198 Ct. Cl. 472, 458, F.2d 1364;

21 B&W Const. Corp., ASBCA 20502, 76-1 BCA ¶ 11693; B.D. Click Co., ASBCA 20616, 77-2 BCA ¶ 12708.

22 E.W Jackson Contracting Co., ASBCA 7267, 62-1 BCA ¶ 3325; F.E. Booker Co., ASBCA 15767, 71-2 BCA ¶ 9025.

23 Overland Electric Co., ASBCA 9096, 64-1 BCA ¶ 4359.

24 Lenry, Inc. v. U.S., 297 F.2d 550 (Ct. Cl. 1962).

25 Frank W. Miller Const. Co., ASBCA 22347, 78-1 BCA ¶ 13039; B.D. Click Co., ASBCA 20616, 77-2 BCA ¶ 12708; Fred G. Koeneke & M.R. Latimer, ASBCA 3163, 57-1 BCA ¶ 1313; F.D. Rich Co., ASBCA 6515, 63-1 BCA ¶ 3710; Warren Painting Co., ASBCA 18456, 74-2 BCA ¶ 10834.

26 D. H. Dave & Gerben Contracting Co., ASBCA 62577, 62-1 BCA ¶ 3493.

27 Nelsen Mortensen & Co. v. U.S., 301 F. Supp. 635 (E.D. Wash. 1969); Hamilton Const. Co., ASBCA 21314, 79-2 BCA ¶ 4095, affd. on reconsideration, 80-2 BCA ¶ 14750.

28 UNITEC Inc., ASBCA 22025, 79-2 BCA ¶ 13923.

29 Glenn Heating, ASBCA 25754,83-1 BCA ¶ 16358.

30 Tobin Quarries Inc. v. U.S., 114 Ct. Cl. 286 (1949); Richard Goettle Inc. v. Tennessee Valley Auth., 600 F. Supp. 7 (N.D. Miss. 1984), 9 CC ¶ 296; W. F. Magann Corp. v. Diamond Mfg. Co., 580 F. Supp. 1299 (D.S.C. 1984); Paul W. Howard Co. v. Puerto Rico Aqueduct Sewer Auth., 744 F.2d 880 (1st Cir. 1984), 8 CC ¶ 499.

31 Bregman Const. Corp., ASBCA 9000, 1964 BCA ¶ 4426; S & M Traylor Bros., ENGBCA 3878 et al., 82-1 BCA ¶ 15484.

32 E. Arthur Higgins, AGBCA 76-148, 76-2 BCA ¶ 12196; Jackson-Swindell-Dressler, ENGBCA 3614, 76-2 BCA ¶ 12222.

33 Wunderlich v. State, 423 P.2d 455 (Cal. 1967); J & T Const. Co., DOTCAB 73-4 et al., 75-2 BCA ¶ 11398; Inland Bridge Co. v. State Hwy. Commn., 227 S.E. 2d 648 (N.C. 1976); Public Constructors, Inc. v. New York, 390 N.Y.S.2d 481 (App. Div. 1977); Titan Atlantic Const. Corp., ASBCA 23588, 82-2 BCA ¶ 15808.

34 ASBCA, 15-1 BCA ¶ 35,939, Optimum Services, Inc.; ASBCA No. 58755, March 25, 2015.

35 Tobin Quarries Inc. v. U.S., 114 Ct. Cl. 286 (1949); E. Arthur Higgins, AGBCA 76-148, 76-2 BCA ¶ 12196; Bernard McMenamy Contractor, Inc., ENGBCA 3413, 77-1 BCA ¶ 12335.

36 Virginia Engrg. Co. v. U.S., 101 Ct. Cl. 516 (1944); Metropolitan Sewerage Commn. v. R.W. Const., Inc., 241 N.W. 2d 371 (Wis. 1976); Norair Engrg. Corp., ENGBCA 3568, 77-1 BCA ¶ 12225; Town of Longboat Key v. Carl E. Widell & Son, 362 So. 2d 719 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1978); Louis M. McMasters, Inc., ASBCA 80-159-4, 86-3 BCA ¶ 19067; Beco Corp. v. Roberts & Sons Const. Co., 760 P.2d 1120 (Idaho 1988), 13 CC ¶ 12.

37 Teodori v. Penn Hills School Dist. Auth., 196 A.2d 306 (Pa. 1964); James Julian, Inc. v. Town of Elkton, 341 F.2d 205 (4th Clr. 1965); Excavation Const. Co., ENGBCA 3646, 77-1 BCA ¶ 12224; Maverick Diversified, Inc., ASBCA 19838, 76-2 BCA ¶ 12104; D. Federico Co. v. New Bedford Redevelopment Auth., 723 F.2d 122 (1st Cir. 1983); Haener v. Ada County Hwy. Dist., 697 P.2d 1184 (Idaho 1985), 9 CC ¶ 209.

38 Mojave Enterprises v. United States, 3 Cl. Ct. 353 (1983); Skip Kirchdorfer, Inc., ASBCA 23443, 79-2 BCA ¶ 14092.

39 Allied Contractors, Inc., ASBCA 2905, 56-2 BCA ¶ 1089; Osberg Const. Co., IBCA 139, 59-2 BCA ¶ 2367; Burl Johnson & Assocs., ASBCA 12497, 68-1 BCA ¶ 6941; Anthony P. Miller, Inc. v. U.S., 422 F.2d 1344 (Ct. Cl. 1970).

40 D. Federico Co. v. New Bedford Redevelopment Auth., 723 F.2d 122 (1st Cir. 1983); Yadkin Inc., PSBCA 2051, 88-3 BCA ¶ 21090.

41 J. E. Robertson Co. v. U.S., 437 F.2d 1360 (Ct. Cl. 1970).

42 ASBCA, 96-1 BCA ¶ 28,229 Queen City, Inc.; ASBCA No. 45755, March 12, 1996.

43 ASBCA, 96-1 BCA ¶ 28,229 Superior Abatement Services, Inc.; ASBCA Nos. 47116, 47117, March 5, 1996.

44 ASBCA, 96-1 BCA ¶ 27,941 Pitt-Des Moines, Inc.; ASBCA Nos. 42838, 43514, 43666, September 26, 1995.

45 ASBCA, 97-2 BCA ¶ 29,136 U.S. General, Inc.; ASBCA No. 4852, July 22, 1997.

46 ASBCA, 97-2 BCA ¶ 29,164 Production Corporation; ASBCA No. 45600, July 29, 1997.

47 JCL-BCA, 05-1 BCA ¶ 32,843 The Clark Construction Group, Inc.; JCL BCA, No. 2003-1, November 23, 2004.

48 DeForest Const. Co., ASBCA 21206, 77-1 BCA ¶ 12361.

49 Skip Kirchdorfer, Inc., ASBCA 23443, 79-2 BCA ¶ 14092.

50 T.J.D. Const. Co., GSBCA 3202, 71-1 BCA ¶ 8673.

51 Paul W. Howard Co. v. Puerto Rico Aqueduct Sewer Auth., 744 F.2d 880 (1st Cir. 1984), 8 CC ¶ 499.

52 E.g., FAR 52.236-2.

53 Tobin Quarries Inc. v. U.S., 114 Ct. Cl. 286 (1949).

54 Clark v. United States, 5 Cl. Ct. 447 (1984), 2 FPD ¶ 186.

55 Majestic Builders Corp. v. Harris, 598 F.2d 238 (D.C. Cir. 1979).

56 State Road Dept. v. Houdaille Indus., Inc., 237 So. 2d 270 (Fla. 1970).

57 J. F. Shea Co. v. United States, 4 C1. Ct. 46 (1983); Guy Atkinson Co., IBCA 385, 65-1 BCA ¶ 4642.

58 Peter Kiewit Sons’ Co. v. U.S., 109 Cl. Ct. 517 (1947); Continental Drilling Co., ENGBCA No. 3455, 75-2 BCA ¶ 11,540-1.

59 United Contractors v. United States, 177 Ct. Cl. 151, 368 F.2d 585, 601 (1966).

60 Kaiser Indus. Corp. v. U.S., 169 Ct. Cl. 310 (1965); J. F. Shea Co. v. United States, 4 C1. Ct. 46 (1983);

61 Foster Const. C.A. v. U.S., 193 Ct. Cl. 587 (1970); Skip Kirchdorfer, Inc., ASBCA 23443, 79-2 BCA ¶ 14092; Mann Const. Co., ASBCA 96-109, 80-2 BCA ¶ 14674.

62 Skip Kirchdorfer, Inc., ASBCA 23443, 79-2 BCA ¶ 14092; Rottaer Elec. Co., ASBCA 20283, 76-2 BCA ¶ 12001.

63 Kaiser Indus. Corp. v. U.S., 169 Ct. Cl. 310 (1965); E.J.T. Const. Co., 206 Ct. Cl. 895 (1975); City of Columbia, Mo. v. Paul N. Howard Co., 707 F.2d 338 (8th Cir. 1983).

64 Sanders Const. Co. & Ray Kiser Const. Co., 220 Ct. Cl. 639 (1979).

65 Pleasant Excavating Co. v. U.S., 229 Ct. Cl. 654 (1981).

66 Fehlhaber Corp. v. U.S., 138 Ct. Cl. 571, cert. denied, 355 U.S. 877 (1957); Souther Paving Corp., AGBCA 74-103, 77-2 BCA ¶ 12813; Torres Const. Co., ASBCA 25697, 84-2 BCA ¶ 17397.

67 Foster Const. C.A. v. U.S., 193 Ct. Cl. 587 (1970); J.F. Whalen, ENGBCA 2859, 69-1 BCA ¶ 7519; J. E. Robertson Co. v. U.S., 437 F.2d 1360 (Ct. Cl. 1970).

68 Gordon H. Ball, Inc., ENGBCA 3563,78-1 BCA ¶ 13055; P.J. Maffel Wrecking Corp., v. U.S., 723 F.2d 913 (Fed. Cir. 1984), 2 FPD ¶ 160, 8 CC ¶ 171.

69 Ragonese v. U.S., 128 Ct. Cl. 156 (1954); Morrison-Knudsen Co. v. U.S., 345 F.2d 535 (Ct. Cl. 1965); Vitro Corp. of Am., IBCA 30366, 67-2 BCA ¶ 6536; Northeast Const. Co., ASBCA 28700, 67-1 BCA ¶ 6195; Maurice Mandel, Inc. v. U.S., 424 F.2d 1252 (8th Cir. 1970); Southwest Engrg. Co. v. U.S., 21 Cont. Cas. Fed. (BNA) ¶ 83909 (Ct. Cl. 1975); Titan Midwest Const. Corp., ASBCA 74517, 81-1 BCA ¶ 15067.

70 S.T.G. Const. Co. v. U.S., 157 Ct. Cl. 409 (1962); Town & Country Pest Control, Inc., ASBCA 40631, 71-1 BCA ¶ 8750.

71 Foster Const. C.A. v. U.S., 193 Ct. Cl. 587 (1970); City of Columbia, Mo. v. Paul N. Howard Co., 707 F.2d 338 (8th Cir. 1983).

72 Highland Const. Co. v. Stevenson, 636 P.2d 1034 (Utah 1981), 6 CC ¶ 68.

73 Turnkey Enterprises Inc. v. United States, 597 F.2d 750 (220 Ct. C1. 1979).

74 Sasso Contracting Co. v. State, 414 A.2d 603 (N.J. 1980).

75 Joseph F. Trionfo & Sons v. Board of Education, 395 A.2d 1207 (Md. 1979), 3 CC ¶ 130; S&M Constructors, Inc. v. City of Columbus, 434 N.E.2d 1349 (Ohio 1982), 6 CC ¶ 284.

76 Callaway Landscape, Inc., ASBCA 22546, 79-2 BCA ¶ 13971; C. & L. Const. Co., ASBCA 22993, 81-1 BCA ¶ 14943, affd. on reconsideration, 81-2 BCA ¶ 15373; B&M Roofing & Painting Co., ASBCA 26998, 86-2 BCA ¶ 18833.

77 Titan Midwest Const. Corp., ASBCA 74517, 81-1 BCA ¶ 15067; Lunseth Plumbing & Heating Co., ASBCA 25332, 81-1 BCA ¶ 15063; White Cap Painters, ASBCA 25364, 81-2 BCA ¶ 15195.

78 Potomac Co., ASBCA 25371, 81-1 BCA ¶ 14950.

79 Hoyer Const. Co., ASBCA 21616, 84-2 BCA ¶ 17249.

80 Callaway Landscape, Inc., ASBCA 22546, 79-2 BCA ¶ 13971; C. & L. Const. Co., ASBCA 22993, 81-1 BCA ¶ 14943, affd. on reconsideration, 81-2 BCA ¶ 15373;

81 Hamilton Const. Co., ASBCA 21314, 79-2 BCA ¶ 4095, affd. on reconsideration, 80-2 BCA ¶ 14750; Blake Const. Co., ASBCA 20747, 83-1 BCA ¶ 16410.

82 Hamilton Const. Co., ASBCA 21314, 79-2 BCA ¶ 4095, affd. on reconsideration, 80-2 BCA ¶ 14750; Blake Const. Co., ASBCA 20747, 83-1 BCA ¶ 16410; Stock & Grove, Inc. v. U.S., 493 F.2d 629 (Ct. Cl. 1974).

83 Raymond Intl. of Del., Inc., ASBCA 13121, 70-1 BCA ¶ 8341; Pavement Specialists, Inc., ASBCA 17410, 73-2 BCA ¶ 10082.

84 Praxis-Assurance Venture, ASBCA 24748, 81-1 BCA ¶ 15028, modified on other grounds, 83-1 BCA ¶ 16411; Alps Const. Corp., ASBCA 16966, 73-2 BCA ¶ 10309; Tutor-Saliba, ASBCA 23766, 79-2 BCA ¶ 14137; Sealtite Corp., ASBCA 26209, 83-2 BCA ¶ 16792; Leiden Corp., ASBCA 26136, 83-2 BCA ¶ 16612; Lyburn Const, Co., ASBCA 29581, 85-1 BCA ¶ 17764.

85 Stuart-Greenwood Const., Inc., ASBCA 33058, 87-1 BCA ¶ 19533.

86 Freeman Elec. Constr. Co. v. United States, 618 7.2d 124 (221 Ct. Cl. 1979), cert. denied, 449 U.S. 825 (1980). American Combustion Inc., ASBCA 32233, 86-3 BCA ¶ 19296.

87 Coleman Elec. Co., ASBCA 4895, 58-2 BCA ¶ 1928; Blankenship Const. Co. v. North Carolina State Hwy. Commn., No. 7526 SC727 (N.C. App. 1976).

88 Charles T. Parker Const. Co. & Pacific Concrete Co., DCAB PR-41, 65-1 BCA ¶ 4780; J. J. Welcome Const. Co., ASBCA 19653, 75-1 BCA ¶ 10997.

89 J. J. Welcome Const. Co., ASBCA 19653, 75-1 BCA ¶ 10997; Sturm Craft Co., ASBCA 27477, 83-1 BCA ¶ 16454.

90 C. & L. Const. Co., ASBCA 22993, 81-1 BCA ¶ 14943, affd. on reconsideration, 81-2 BCA ¶ 15373; Hoyt Harris Inc., ASBCA 23543, 81-1 BCA ¶ 14829; Leiden Corp., ASBCA 26136, 83-2 BCA ¶ 16612.

91 Sturm Craft Co., ASBCA 27477, 83-1 BCA ¶ 16454.

92 C. & L. Const. Co., ASBCA 22993, 81-1 BCA ¶ 14943, affd. on reconsideration, 81-2 BCA ¶ 15373; DeMauro Const. Corp., ASBCA 17029, 77-1 BCA ¶ 12511; AAAA Enterprises, Inc., ASBCA 28172, 86-1 BCA ¶ 18628.

93 C. & L. Const. Co., ASBCA 22993, 81-1 BCA ¶ 14943, affd. on reconsideration, 81-2 BCA ¶ 15373; AAAA Enterprises, Inc., ASBCA 28172, 86-1 BCA ¶ 18628.

94 C. & L. Const. Co., ASBCA 22993, 81-1 BCA ¶ 14943, affd. on reconsideration, 81-2 BCA ¶ 15373.

95 Sealtite Corp., ASBCA 26209, 83-2 BCA ¶ 16792; Hoyt Harris Inc., ASBCA 23543, 81-1 BCA ¶ 14829; Robert McMullan & Son, Inc., ASBCA 22168, 78-2 BCA ¶ 13228; Covco Hawaii Corp., ASBCA No. 26901, 83‑2 B.C.A. (CCH) ¶ 16,554 (1983); Quiller Const. Co., ASBCA 25980, 84-1 BCA ¶ 16998.

96 Shank-Artukovich v. U.S., 13 Cl. Ct. 346 (1987), 6 FPD ¶ 130, affd. without opinion, 848 F.2d 1245 (Fed. Cir. 1988), 7 FPD ¶ 57.

97 B&M Roofing & Painting Co., ASBCA 26998, 86-2 BCA ¶ 18833; Fort Sill Assocs., ASBCA 7482, 63-1 BCA ¶ 3869, affd., 183 Ct. Cl. 301 (1968); Kahaluu Const. Co., ASBCA 31187, 89-1 BCA ¶ 21308.

98 Erickson-Shaver Contracting Corp. v. U.S., 9 Cl. Ct. 302 (1985), 5 FPD ¶ 5.

99 Leiden Corp., ASBCA 26136, 83-2 BCA ¶ 16612; Hurlen Const. Co., ASBCA 31069, 86-1 BCA ¶ 18690; Robert D. Carpenter, Inc., ASBCA 22297, 79-1 BCA ¶ 13675.

100 Nelsen Mortensen & Co. v. U.S., 301 F. Supp. 635 (E.D. Wash. 1969); Hamilton Const. Co., ASBCA 21314, 79-2 BCA ¶ 4095, affd. on reconsideration, 80-2 BCA ¶ 14750.

101 Quiller Const. Co., ASBCA 25980, 84-1 BCA ¶ 16998; Warren Painting Co., ASBCA 18456, 74-2 BCA ¶ 10834.

102 MC Co., ASBCA 21403, 78-2 BCA ¶ 13313.

103 Arthur Painting Co., ASBCA 20267, 76-1 BCA ¶ 11894.

104 Blount Bros. Corp., ENGBCA 2803, 70-1 BCA ¶ 8256.

105 Norair Engrg. Corp., ENGBCA 3568, 77-1 BCA ¶ 12225; Nelson Bros. Const. Co. v. U.S., 225 Ct. Cl. 702 (1980).

106 Premier Elect. Const. Co., FAACAP 66-10, 65-2 BCA 5080.

107 Pritz Assocs., Inc., VACAB 521, 66-1 BCA ¶ 5402.

108 M. Williams & Sons, Inc., VACAB 546, 66-2 BCA ¶ 5988.

109 R. A. Heintz Const. Co., ENGBCA 338O, 74-1 BCA ¶ 10562.

110 Northwest Painting Service, Inc., ASBCA 27854, 84-2 BCA ¶ 17474; J. J. Barnes Const. Co., ASBCA 27876, 85-3 BCA ¶ 18503; Lyburn Const, Co., ASBCA 29581, 85-1 BCA ¶ 17764.

111 Robert McMullan & Son, Inc., ASBCA 22168, 78-2 BCA ¶ 13228; Ellis Const. Co., ASBCA 19541, 75-1 BCA ¶ 11238; James E. McFadden, ASBCA 19931, 76-2 BCA ¶ 11983, affd, on reconsideration, 79-2 BCA ¶ 13928; Commercial Mechanical Contractors, Inc., ASBCA 25695, 83-2 BCA ¶ 16768; Fred A. Arnold, Inc., ASBCA No. 20150, 84‑3 BCA (CCH) ¶ 17,624 (1984);

112 Callaway Landscape, Inc., ASBCA 22546, 79-2 BCA ¶ 13971.

113 C. & L. Const. Co., ASBCA 22993, 81-1 BCA ¶ 14943, affd. on reconsideration, 81-2 BCA ¶ 15373; Joseph Morton Co., ASBCA 19793, 78-1 BCA ¶ 13173, modified on other grounds, 80-2 BCA ¶ 14502.

114 DOT-BCA, 96-1 BCA ¶ 28,033 Betancourt & Gonzalez, S.E.; DOT BCA Nos. 2785, 2789, 2799, October 30, 1995.

115 White Cap Painters, ASBCA 25364, 81-2 BCA ¶ 15195; Fairbanks Builders, ASBCA 18288, 74-1 BCA ¶ 1097; Covco Hawaii Corp., ASBCA No. 26901, 83‑2 B.C.A. (CCH) ¶ 16,554 (1983); TGC Contracting Corp., ASBCA 24441, 83-2 BCA ¶ 16764, affd., 736 F.2d 1512 (Fed. Cir. 1984), 2 FPD ¶ 194.

116 Schmelig Const. Co. v. State Hwy. Commn., 543 S.W.2d 265 (Mo. 1976); Jacksonville Port Authority v. Parkhill-Goodloe Co., 362 So. 2d 1009 (Fla.1978), 2 CC ¶ 314.

117 Sand Key Const. Co. v. State, 399 P.2d 1002 (Mont. 1965); Robert E. McKee, Inc. v. City of Atlanta, 414 F. Supp. 957 (N.D. Ga. 1976).

118 Ragonese v. U.S., 128 Ct. Cl.156 (1954); T.F. Scholes, Inc. v. U.S., 174 Ct. Cl. 1215 (1966); Sanders Co. Plumbing & Heating, Inc. v. City of Independence, 694 S.W.2d 841 (Mo. Ct. App. 1985); P.T.&L. Const. Co. v. New Jersey Dept. of Transportation, 531 A. 2d 1330 (N.J. 1987).

119 Raymond Intl., Inc. v. Baltimore County, 412 A.2d 1296 (Md. 1980).