January 20, 2025

Modified Total Cost Method for Calculating and Presenting Damages in a Construction Claim

When a contractor’s costs exceed its contract amount on a construction project due to owner-caused impacts, the contractor can choose from several damages methods in seeking equitable compensation.

If the claimant can show 1) entitlement to recover for the other party’s wrongful conduct, and 2) damage incurred because of that wrongful conduct, the claimant may recover even though the amount of the damage is uncertain or is based on estimates. There are several methods currently in use for the calculation of recoverable damages.

Previous blog posts addressed the Total Cost method. This blog post discusses the Modified Total Cost method, and future blog posts will discuss the Jury Verdict method, Quantum Meruit, the A/B Estimate method, the Delta Estimate method, and the Discrete Damages/Cost Variance Analysis method.

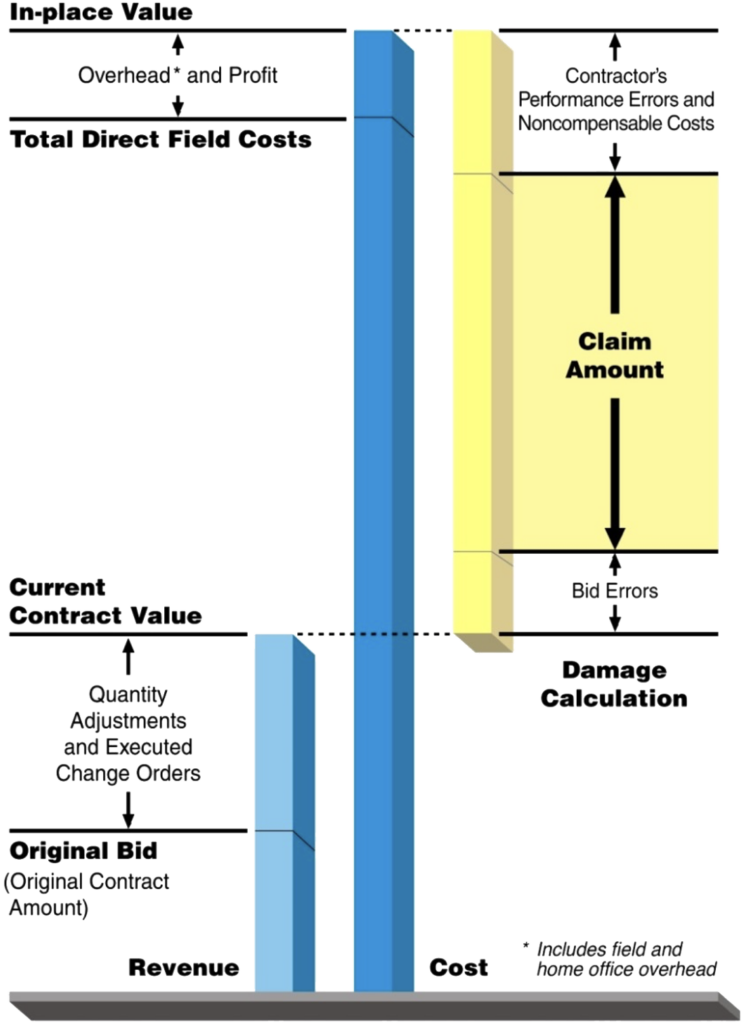

The Modified Total Cost approach is a damages analysis method whereby the claim amount is produced by calculating the difference between an adjusted in-place value and an adjusted bid amount. The adjusted in-place value is determined by taking the project’s in-place value (total field costs plus overhead, profit, and bond) and adjusting it downward for identified contractor-caused performance errors and other noncompensable costs.1 The adjusted bid amount is determined by adjusting the original bid (contract) amount for executed Change Orders and identified bid errors.

As Figure 1 shows, the Modified Total Cost method is similar to the Jury Verdict method, except that the contractor presents the claim value by adjusting the total costs for noncompensable costs and bid errors rather than the “jury” or “trier of fact” making these adjustments.

Figure 1: Modified Total Cost Method

The Modified Total Cost method is held in higher regard than the Total Cost method, but the contractor must still satisfy the four elements applicable to the Total Cost approach,2 namely the impracticability of proving actual losses with a reasonable degree of accuracy, the reasonableness of the bid/budget costs, the reasonableness of the contractor’s actual costs, and the lack of contractor responsibility for additional costs.

Use of the Modified Total Cost approach is also advantageous to a contractor on those construction cases with schedule delays, lost productivity, and numerous unresolved claims that are mostly intertwined and contain inextricable elements of changes and impacts to the unchanged work. In these cases, it is usually impossible or highly impractical to keep accurate records by which the contractor can link the costs incurred to specific problems encountered on the job. In addition, this approach is best suited to those cases where it would be highly impractical to even attempt to compute damages by any other method. The contractor must, however, identify and accurately quantify its bid and performance errors to use this method.

Because the Modified Total Cost approach may produce a higher claim amount than other methods, the owner may be disadvantaged. However, one advantage that the owner enjoys is that the court usually requires the contractor to disclose its cost records. This affords the owner the opportunity to perform its own damage analysis in preparation for defense of the claim. By analyzing the contractor’s actual cost records, the owner may be able to demonstrate additional cost overruns that are attributable to bid errors or contractor execution errors. The owner’s analysis may also be able to show that certain cost accounts showing cost overruns have no relationship to owner-caused problems or, at least, both the owner and contractor impacted certain activities for which the contractor is inappropriately blaming the owner for 100 percent of the cost overrun.

One board adopted a Modified Total Cost approach in Robert McMullan & Sons, Inc., finding that the contractor’s claim arose almost from the beginning of the contract, continuing and enlarging itself every day of the project. The board stated that to attempt to segregate delay and lost time, set up and break down estimates, and evaluate interferences and loss of efficiency as opposed to normal time would be a wasteful exercise because in the end, the result should approach the total cost experienced. It was impractical if not impossible to distinguish with any degree of accuracy the contract work from extra work.3

Another board evidenced this line of reasoning in its decision regarding the appeal of Sovereign Construction Company, Ltd.:

Inefficient work is an intangible commodity. It is not possible to make a direct measurement of it. In identifying and measuring inefficiency a comparison must be made to some accepted standard. In this appeal we are unaware of any better method by which the appellant could establish additional costs attributable to inefficiency than by establishing what the work reasonably should have cost and what the work did in fact cost. Of course, the actual costs are subject to reduction if they include elements for which the Government is not responsible.4

One criticism sometimes proffered by an owner in a complex loss of productivity case may be that the contractor ought to have performed the changed or additional work in a different manner and should have managed the problem less expensively by performing in a different fashion.

The decisional law has not supported this Monday-morning quarterbacking. In Great Lakes Dredge & Dock Co. v. United States,5 the government urged that the contractor ought to have used a different method of solving a difficult problem for which the government had payment responsibility under the contract. The court said that it was not interested in a hypothetical alternative solution.6 The court then adopted a Modified Total Cost approach, stating:

In order to show what its increased costs were the plaintiff has produced proof to show what its estimated costs were and what its actual costs were. The difference it has adjusted by certain errors that it admits it had made in making up its estimate, and also certain costs which it admits were not attributable to the encountering of this subterranean water.7

The court found that the contractor had underbid the project and, accordingly, the court adjusted the plaintiff’s bid. The court then compared the adjusted bid to the cost of performing the work. The court made adjustment for costs incurred that were not the government’s fault as the contractor suggested.8

In another instance, the Court of Claims faced a case in which the plaintiff contractor relied on a Modified Total Cost approach. The court stated:

In essence, what plaintiff seeks to recover as an equitable adjustment is the difference between the total costs it actually incurred and what it ‘should have’ cost to produce the 200,000 MK-8 cartridges had there been no defective specifications.

Teledyne is confronted with an accusation that some of its costs should be disallowed. However, no reason whatsoever has been given as to why these costs should be disallowed. Other than the defective specifications, all other possible reasons for these additional costs have been eliminated. In requiring plaintiff to prove still more (more than it has already proven), in the absence of evidence by the Government as to why the costs should be disallowed, the Board, in effect, applied a standard of proof approaching “beyond a reasonable doubt.”9

The court accepted the approach and held for the plaintiff contractor.

The Modified Total Cost approach has met the approval of the boards and courts. Although it is not mathematically certain, such certainty is not required. In the case of Elete, Inc. v. S.S. Mullen, Inc., the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit articulated the general rule regarding whether exact ascertainment of damages is required:

The difficulty of ascertainment of the amount of damage is not to be confused with the right of recovery. The rule is that, if the plaintiff produced the best evidence available and if it is sufficient to afford a reasonable basis for estimating his loss, he is not to be denied a substantial recovery because the amount of the damage is incapable of exact ascertainment.10

A New York court also discussed this principle in S. Leo Harmonay Inc. v. Binks Manufacturing Company:

It is fundamental to the law of damages that one complaining of an injury has the burden of proving the extent of harm suffered; delay damages are no exception…. On the other hand, courts have often recognized that the extent of harm suffered as a result of delay, such as the loss of efficiency claim in issue, may be difficult to prove. Thus, courts have recognized that a plaintiff may recover even where it is apparent that the quantum of damage is unavoidably uncertain, beset by complexity, or difficult to ascertain, if the damage is caused by the wrong. The law is realistic enough to bend to necessity in such cases.11

Damages need not be proven with mathematical certainty.12 The Modified Total Cost approach utilizes the best available information to determine as closely as possible what the damages should be. “Moreover, evidence of damages may consist of probabilities and inferences.”13 The ASBCA has noted:

Where, however, the contractor has proved that it suffered extra expenses by reason of changes, delays by the Government, etc. the mere fact that the amount of an equitable adjustment cannot be computed with mathematical certainty does not necessarily defeat recovery. If a fair and reasonable approximation can be determined, the Courts and this Board have done so.14

A 2009 New Jersey court categorically rejected a general contractor’s attempt to use the Modified Total Cost method to prove its delay damages in claims asserted against the design consultant on a public construction project. The court similarly rejected the contractor’s attempt to use a cumulative impact theory of causation, which the plaintiff described as a “ripple effect” attributable to numerous design deficiencies, finding that there were “substantial questions” regarding the contractor’s ability to show causation. While the court concluded that the contractor could proceed to trial on other aspects of its claim, the court cautioned that it would not allow the contractor to avoid its own negligence or other potential causes of delay and damage unrelated to the designer’s negligence by asserting that there was a “cumulative impact” of delay and damages that was solely the designer’s fault.15

However, a 2010 California Court of Appeal case unequivocally establishes the Modified Total Cost theory of damages as a viable remedy for California contractors.16 The appellate court found that where no contractual requirement exists for a contractor to document its actual costs, that contractor may be able to recover for work it performed in good faith using the Modified Total Cost method. During the subject wastewater treatment plant project, the owner issued over 300 Change Orders containing more than 1,000 changes to the plans and specifications. The appellate court found that the Modified Total Cost theory was valid, depending on interpretation of the contractual requirements for documentation of the actual costs of Change Orders. Under the Total Cost method, damages are determined by subtracting the contract amount from the total cost of the contractor’s performance. Under the Modified Total Cost method, if the contractor is responsible for some of its increased cost of performance, then those costs are subtracted from the contractor’s damages to arrive at the Modified Total Cost value. The court found that the contractor was not contractually required to document its actual costs (which the contractor contended was not possible), and that the contractor could use engineering estimates to prove its claims under a Modified Total Cost method, provided those estimates were the best evidence available.

In 2011, the Washington Court of Appeals determined that a contractor’s use of the Modified Total Cost method17 was appropriate because the contractor’s expert considered the cost for which the contractor was responsible and the financial impact of the contractor’s delay. The contractor had also shown that its bid was reasonable.

1 See Great Lakes Dredge & Dock Co. v. United States, 96 F. Supp. 923 (119 Ct. Cl. 1951); Sovereign Construction Company, Ltd., ASBCA No. 17792, 75-1 BCA ¶ 11,251, at 53,606.

2 See AMEC Civil, LLC v. DMJM Harris, Inc., Civil Action No. 06-64 (FLW), U.S. District Court, D. New Jersey (June 2009) (citing Propellex, 342 F.3d at 1339; Servidone, 931 F.2d at 861-62; and S. Comfort Builders, 67 Fed. Cl. at 146-47). See, also, Youngdale & Sons Constr. Co. v. United States, 27 Fed Cl. 516 (1993) at 541 (citing Servidone, 931 F.2d at 861): “The modified total cost method is simply the total cost method modified or adjusted for any deficiencies in the plaintiff’s proof in satisfying the four requirements of said method.”

3 See Robert McMullan & Sons, Inc., ASBCA No. 19129, 76-2 BCA ¶ 57,947.

4 Sovereign Construction Company, Ltd., ASBCA No. 17792, 75-1 BCA ¶ 53,606.

5 Great Lakes Dredge & Dock Co. v. United States, 96 F. Supp. 923 (119 Ct. Cl. 1951).

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Teledyne McCormick Selph v. U. S., 588 F.2d 808, 810 (Ct. Cl. 1987).

10 Elete, Inc. v. S.S. Mullen, Inc., 469 F.2d 1 127 (1972) at 1131.

11 S. Leo Harmonay Inc. v. Binks Manufacturing Company, 597 F. Supp. 1014 (S. D. N.Y. 1984) aff’d. 762 F.2d. 990 (2d Cir. 1984).

12 See E.C. Ernst, Inc. v. Koppers Co., Inc., 626 F.2d 324, 327 (3rd Cir. 1980).

13 E.C. Ernst, Inc. v. Koppers Co., Inc., 626 F.2d 324, 327 (3rd Cir. 1980).

14 Drexel Dynamic Corp., 67-2 BCA ¶ 6,410, pages 29,698, 29,699 (ASBCA 1967).

15 See AMEC Civil, LLC v. DMJM Harris, Inc., Civil Action No. 06-64 (FLW), U.S. District Court, D. New Jersey (June 2009).

16 See Dillingham-Ray Wilson v. City of Los Angeles (2010) 182 Cal.App.4th 1396.

17 See Coastal Constr. Grp., Inc. v. Stellar J. Corp., Court of Appeals of Washington, Division One, No. 66932-0-1, October 2011.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Blog

Discover industry insights on construction disputes and claims, project management, risk analysis, and more.

MORE

Articles

Articles by our engineering and construction claims experts cover topics ranging from acceleration to why claims occur.

MORE

Publications

We are committed to sharing industry knowledge through publication of our books and presentations.

MORE

RECOMMENDED READS

Total Cost Method for Calculating and Presenting Damages in a Construction Claim: Part 1

This blog post discusses the Total Cost method, including elements of proof, theoretical bases, and prerequisites.

READ

Total Cost Method for Calculating and Presenting Damages in a Construction Claim: Part 2

This blog post addresses topics related to the Total Cost method, including the Total Cost cumulative impact claim.

READ

Methods for Calculating and Presenting Damages in a Construction Claim

This blog post describes seven methods for calculating and presenting damages in a construction claim and how to choose one.

READ