January 6, 2025

Total Cost Method for Calculating and Presenting Damages in a Construction Claim: Part 1

When a contractor’s costs exceed its contract amount on a construction project due to owner-caused impacts, the contractor can choose from several damages methods in seeking equitable compensation.

If the claimant can show 1) entitlement to recover for the other party’s wrongful conduct, and 2) damage incurred because of that wrongful conduct, the claimant may recover even though the amount of the damage is uncertain or is based on estimates. There are several methods currently in use for the calculation of recoverable damages.

This blog post will discuss the Total Cost method of calculating damages, including elements of proof, theoretical bases, and prerequisites. The next blog post will address other topics related to the Total Cost method, including the owner’s failure to provide an alternate method and the Total Cost cumulative impact claim.

Future blog posts will discuss the Modified Total Cost method, the Jury Verdict Method, Quantum Meruit, the A/B Estimate Method, the Delta Estimate Method, and the Discrete Damages/Cost Variance Analysis method.

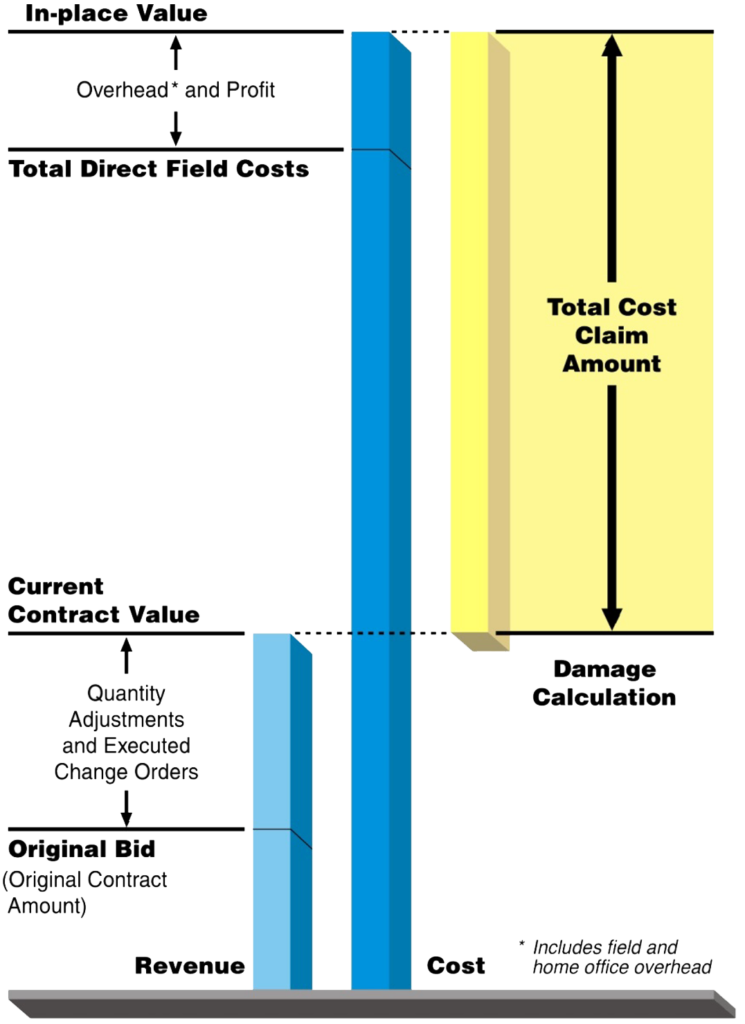

The Total Cost method involves a simple claim calculation based upon the assumption that all cost overruns are the result of the owner’s actions. The contractor claims the difference between the costs it expended and the costs it was paid and adds applicable overhead and profit. American and international courts have rejected the use of the Total Cost method for factual, not legal, reasons, rarely embrace Total Cost calculations, and do so only if the claimant sets forth certain elements of proof.

Most American courts disfavor the Total Cost method:

This measure of damages has not been favored by the courts.1

Our opinion in Great Lakes Dredge & Dock Co. v. United States was not intended to give approval to this method of proving damage, except in an extreme case and under proper safeguards.2

[W]e view basing damages on the difference between bid estimate and actual costs with trepidation.3

Figure 1 illustrates the Total Cost method.

Figure 1: Total Cost Method

Elements of Proof

In 1968, the U.S. Court of Claims4 set out the following elements of proof that a claimant must demonstrate to prevail on a Total Cost claim for damages:

- The nature of the [claimant’s] particular losses make it impossible or highly impracticable to determine them with a reasonable degree of accuracy;

- The claimant’s bid or estimate was realistic;

- Its [the claimant’s] actual costs were reasonable; and

- It [the claimant] was not responsible for the added expenses.

The court adjudicating WRB Corp. v. United States wrote:

This theory [total cost] has never been favored by the court and has been tolerated only when no other mode was available and when the reliability of the supporting evidence was fully substantiated.5

Thus, element no. 1 sets forth two requirements:

- Total Cost is to be used only as a fail-safe; and

- It must rest on reliable supporting evidence.

Other courts have widely followed these requirements. The owner’s classic argument is that the contractor has not shown that the owner’s breach caused the contractor’s excess costs, and that the contractor has only shown its final costs. If the contractor merely measures its cost overruns for the entire project by summing overruns from each work activity, the contractor is not providing proof that the owner’s breach caused the increased costs; it is merely breaking the overruns into smaller components. Unless it can show some “Measured Mile” effect for each individual work activity, there is no proof that a particular breach caused the cost overrun. If a court determines that it is impractical to prove losses directly, then the court finds no “Measured Mile” method exists to ensure that the claim is reasonably certain. With respect to proof of causation, the causal connection that the overrun resulted from a specific breach is implied because of the difficulty of actual proof.

Elements 2 through 4 above are derived from a 1955 Court of Claims’ criticism of the Total Cost method:

This method of proving damage is by no means satisfactory, because, among other things, it assumes plaintiff’s costs were reasonable and that plaintiff was not responsible for any increases in cost, and because it assumes plaintiff’s bid was accurately computed, which is not always the case, by any means.6

Thus, in element 2, courts are concerned that contractors may try to turn a loss into a gain when a contractor has underbid a job. A contractor usually prepares the bid estimate in support of its commercial tender for a project, and it forms the basis for the preparation of a control budget that is used for project cost control. The bid estimate should include sufficient costs for project engineering, procurement, and construction. The bid estimate may also include start-up, pre-commissioning, and commissioning costs if these activities are part of the contract scope of work. The estimate should be based upon the contractor’s knowledge of, and experience on, similar construction projects, its proposed construction means and methods and work plan, its knowledge of the project scope of work and regulatory requirements, and its relationships and experience with subcontractors and suppliers.

The value and accuracy of the bid estimate are based upon and should consider uncertainties and assumptions related to project scope, duration, and labor productivity, and the status of various project development and definitional considerations known at the time that the contractor tenders its commercial proposal. As such, the bid estimate should include sufficient allowances (design development allowances, for example) and contingency to provide for estimate uncertainties.

For element 3, a court provided a definition of the reasonableness of actual costs: “[A] reasonable basis for computation and the best evidence which is obtainable under the circumstances of the case, and which will enable the trier to arrive at a fair approximate estimate of loss is sufficient proof.”7 As stated earlier, damages from loss of productivity may be difficult to prove and, therefore, it may be difficult to establish the reasonableness of the actual costs.

For example, in Aetna Casualty and Surety Co. v. George Hyman Construction Co.,8 the subcontractor, which the surety represented in this case, was contracted to perform electrical work on an Amtrak rail station. The plaintiff claimed loss of productivity under the “cumulative impact” theory, but the court rejected the plaintiff’s claim and stated that “[T]he mere expression of an estimate as to the amount of productivity loss by an expert witness with nothing to support it will not establish the fundamental fact of resultant injury nor provide a sufficient basis for making a reasonable approximation of damages.”9

Regarding element no. 4, a 2002 California court held that the contractor failed to satisfy that it was not responsible for the increased costs.10

Thus, the Total Cost method may be used as a last resort to ensure equity when the factual information is dependable and when no other method to calculate damages can be used. However, courts prefer the discrete calculation of damages:

The proper measure of damages is the amount of the contractor’s extra costs directly attributable to the [owner’s] breaches. Obviously, the preferable method for calculating such losses would be to itemize and total the cost of each piece of equipment or material and each man-hour necessitated by the unanticipated conditions encountered in performing the contract.11

Theoretical Bases

The Total Cost method is based on the premise that damages do not have to be calculated with exactitude and upon the courts’ concern with ensuring that injured parties are compensated. A 1986 Pennsylvania court invoked a widely accepted American damage rule:

[M]ere uncertainty as to the amount of damages will not bar recovery where it is clear that damages were the certain result of [the owner’s] conduct. [emphasis added]12

Previously, a 1955 court wrote:

The plaintiff must prove its damages with reasonable certainty, but they do not have to be proved with absolute certainty. It is sufficient if plaintiff furnishes a reasonable basis for its computation, even though the result is only approximate.13

To ensure that a claimant was not denied a recovery because of calculation problems, another court stated:

[Total cost method] is premised on the fact that where a contractor is entitled to an adjustment, the governmental body should not be exonerated merely because the contractor is unable to prove his increased costs with precision.14

Prerequisites

Even when properly used, the Total Cost method is the last step, not the first or only step in claim preparation. The Total Cost becomes a relevant issue only after the claimant has proved entitlement and cause-effect. Total Cost is a method for calculating damages and not a method of proving liability.

The “total cost plus profit” theory of computing damages…assumes that defendant is in fact liable for all the injuries sustained….15

1 John F. Harkins Co. v. School Dist. of Philadelphia, supra, 460 A.2d at 263.

2 F.H. McGraw and Co. v. United States, 130 F. Supp. 394, 397, 398, 400 131 Ct. Cl. 501 (1955) at 400.

3 Oliver-Finnie Co. v. United States, 279 F.2d 498, 506, 150 Ct. Cl. 189 (1960).

4 See WRB Corp. v. United States, 183 Ct. Cl. 409, 1968 WL 9146 at paragraph 8.

5 Ibid.

6 F.H. McGraw and Co. v. United States, 130 F.Supp. 394, 397, 398, 400 131 Ct. Cl. 501 (1955).

7 Bagwell Coatings, Inc. v. Middle S. Energy, Inc., 797 F.2d 1298, 1309 (5th Cir. 1986).

8 Aetna Casualty & Surety Co. v. George Hyman Construction Co., U.S. Dist., LEXIS 22627 (E.D. Pa. 1998).

9 Aetna Casualty & Surety Co. v. George Hyman Construction Co., U.S. Dist., LEXIS 22627 (E.D. Pa. 1998) at 262 (citing Luria Bros. & Co. v. United States, 177 Ct. Cl. 676, 369 F.2d 701,707, 713 (1966).

10 See Amelco Elec. v. City of Thousand Oaks, 98 Cal. Rptr. 2d 159 (Cal Ct. App. 2000).

11 State Highway Comm’n of Wyoming v. Brasel & Sims Construction Co., Inc., 688 P.2d 871, 877 (Wyo. 1984).

12 Larry Armbruster & Sons, Inc. v. State Public School Bldg. Auth., 95 Pa. Commw. 310, 505 A.2d 313 (1986); Pugh v. Holmes, 486 Pa. 272, 405 A.2d 897 (1979).

13 F.H. McGraw and Co. v. United States, 130 F.Supp. 394, 397, 398, 400 131 Ct. Cl. 501 (1955). Also see Rubin, The Total Cost Method of Computing an Equitable Adjustment – An Analysis, 26 Fed.B.J. 303, 304 (1966).

14 John F. Harkins Co. v. School Dist. of Philadelphia, 313 Pa. Super. 425, 460 A.2d 260, 263 (1983).

15 Wunderlich Contracting Co. v. United States, 351 F.2d 956, 965, 173 Ct. Cl. 180 (1965) at p. 12 (Westlaw print).

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Blog

Discover industry insights on construction disputes and claims, project management, risk analysis, and more.

MORE

Articles

Articles by our engineering and construction claims experts cover topics ranging from acceleration to why claims occur.

MORE

Publications

We are committed to sharing industry knowledge through publication of our books and presentations.

MORE

RECOMMENDED READS

Methods for Calculating and Presenting Damages in a Construction Claim

This blog post describes seven methods for calculating and presenting damages in a construction claim and how to choose one.

READ

Construction Claims Analysis Checklist

This article sets forth the basic information and tasks in performing a construction claims analysis whether one is preparing a claim or defending against one.

READ

Long International’s Schedule and Delay Analysis Methodologies

Long International explains its detailed schedule analysis methodology using a construction delay claim on a hypothetical wastewater treatment plant project.

READ